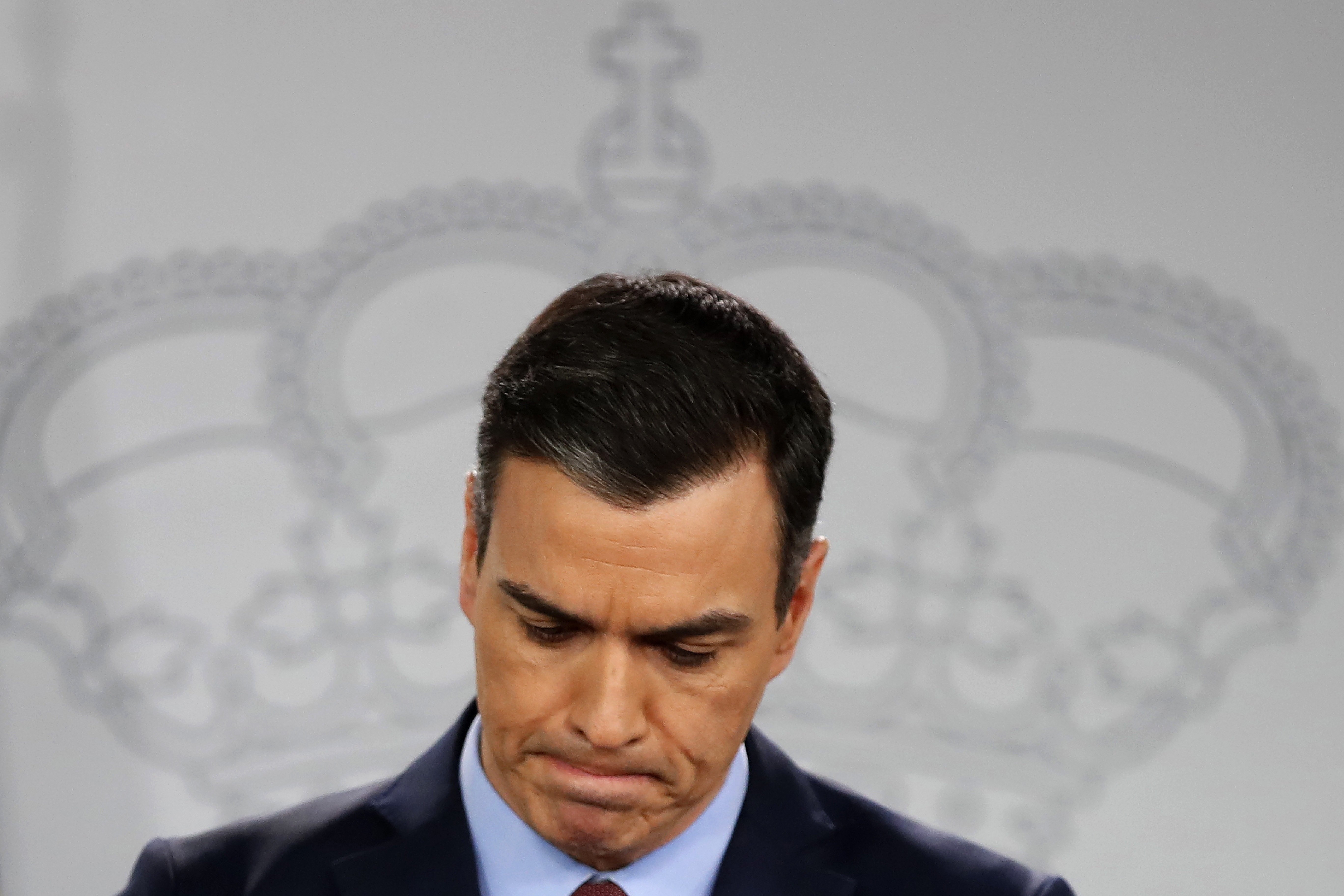

The crash programme announced by the Spanish government to fight against the economic consequences of Covid-19 leaves much in the air and one thing certain: it's late. Pedro Sánchez has announced that up to 200 billion euros will be mobilized to deal with the effects of the pandemic, an amount that is quite in line with other European economies, but experts warn that "it's just not very clear" how it will be implemented. At the same time, a common fear: will we repeat the mistakes of the 2008 crisis?

In the first place, one of the plan's most anticipated measures - which has also raised the most doubts - is the moratorium to banks on mortgages payments "by the most vulnerable families". Several economists have questioned this point: "In a situation like this, who are the vulnerable?" asked economist Xavier Sala-i-Martín on social media. In the same vein, Anton Gasol, dean of the Catalonia Economists College, explains, "in this crisis, everyone will lose, and the only thing that has to be ensured is that it is fair."

The 200 billion in the government package represents approximately 20% of Spain's GDP. Of this sum, according to Sánchez, 117 billion will come from public funds, and the remaining 83 billion from private, and this is, in the words of the Spanish prime minister, "the largest mobilization of economic resources in the history of Spain in a very short space of time."

At the same time, the Spanish executive has also assured that as long as the crisis goes on, "mortgage foreclosure evictions will not be possible", but there is another doubt: rents. "We are told about mortgages, but no comment has been made on people who rent. There are many who will not be able to pay what they owe their landlords because they won't make ends meet." What will happen to this part of society? More uncertainty.

It should be noted, however, that the bulk of aid is for companies - mainly SMEs and the self-employed - to avoid an increase in unemployment. In this regard, the Spanish government will create a line of guarantees worth 100 billion euros. At the same time, also in the line of avoiding definitive layoffs, procedures will be put in place to make possible temporary redundancy agreements (ERTOs, in their Catalan acronym) which major employers associations have repeatedly called for at both Catalan and Spanish levels. Thus, it will be the state that pays salaries and contributions, as well as unemployment benefits.

In fact, the trickle of companies that have begun to take such measures is turning into a flood. In Catalonia alone, the labour ministry has already registered 206 ERTO applications arising from the crisis, affecting a total of 24,337 workers. On the face of it, economist Santiago Niño Becerra is skeptical: "When the virus leaves, you should compare the staff numbers of these companies, before and after."

Comparisons with other countries

Several economists assert that the measures established, despite being late, "are on the right track" but fall a little short compared to decisions taken in other European countries. One only has to look at Italy, which today announced a ban on companies firing workers due to the coronavirus crisis, a measure that has been extended for up to two months. This is one of the actions included in a decree-law pushed through by the Italian government, with an assistance package of up to 25,000 million euros, which will mobilize resources worth up to 350,000 million, much more than Sánchez's proposal.

In France, they didn't have to wait until they reached nearly 12,000 Covid-19 cases for the government to announce its lockdown and suspend tax and social contribution payments, as well as water, electricity and gas bills. In addition, Emmanuel Macron has also suspended rent payment for small businesses, freelancers and merchants of all kinds, and to activate this, all you have to do is send an email.

In Germany, the government has made available a 500 billion euro fund in loans to companies, whether large, medium, small or self-employed. This figure is five times that proposed by the Spanish government.

Finally, in Denmark, an agreement has been reached between government, companies and workers to pay the salaries of those who will not be able to do their jobs. This is the example Sala-i-Martín gives to illustrate how this could be done: 75% of salary is paid by the state, 25% by companies and workers sacrifice five days of holidays. In return, companies promise not to fire anyone and everyone will be able to resume their jobs when the pandemic is over.

Storm of criticism of the EU

The central criticism of the management of this crisis targets the European Union. Economist Santiago Niño-Becerra has been outspoken on social media: "It gives me the feeling that we are returning to 2008, the Zapatero government's Plan E; and you know how that ended: with a huge deficit that resulted in an out of control public debt. If this current situation, classified as very serious, does not lead the EU to formulate a common fiscal policy with common rules against tax fraud and with a single budgeting and control strategy, we better forget this 'one Europe' that so much is said about."

He is not the only one. Anton Gasol is also critical and says that "Sánchez has done much better than the European Union is doing, which is putting in circulation 12 billion euros and 100 billion in guarantees, which is equivalent to 1% of the EU's GDP". About that, he states that "the European Central Bank's repetition of the famous mantra 'whatever it takes' is not enough: this has to be materialized."

And the double criticism of Sala-i-Martín: "Because the Spanish state has not done its homework in a boom period and it has not "saved" in order to deal with situations like this, all the extra expense will have to be financed with ECB credits. European authorities should come out of their caves and make the quantitative easing policy explicit." He says "the bill to be paid will be large and the amount of money the ECB will have to print will be, too".