It was the year 1469 and Ferran and Isabel, princelings to the royal houses of Catalonia-Aragon and Castile-Leon, were married privately. Neither pomp nor ceremony. While it is true that Europe was still crippled by the terrible effects of the plague, it is surprising that the two alleged crafters of Hispanic union —sacred symbols for contemporary Spanishness, known as the Catholic Monarchs— should be hurriedly married in secret. A bizarre situation that reveals the fabrication of the false myth of Spanish unity built upon that marriage, with the legend Tanto Monta, Monta Tanto (“It makes no difference, It’s all the same”, i.e. that both monarchs had identically equivalent power and position). It is the false myth of “the oldest nation in Europe” always on the lips of Spanish leaders, both past and present.

The journey to power

To reach their respective thrones, Ferran and Isabel had to steer around countless obstacles in a path full of bends and turns worthy of a good spy story. When they were married, neither boasted the condition of heir to the throne. At least they were not recognised as such. In Castile, those who favoured Isabel were liquidating —physically— all those who preceded her in the lineage. In Catalonia, on the other hand, Ferran supporters wove a network of alliances —negotiated with all parts of society— to support their candidate. The celebrated Catalan transverseness inspired by Italian finezza. The culture of stepping aside that has endured with time. Details that explain, too, the opposing political cultures that differentiated —and still differentiate— Castile and Catalonia

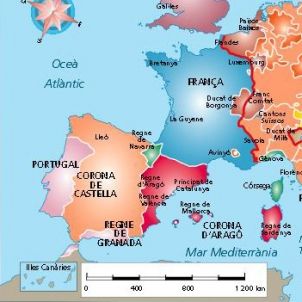

In 1474 —just five years after that express wedding— Isabel had already buried all her rivals. She was crowned queen of Castile and Leon. All in one package. Meanwhile, Ferran had to wait five years longer —the tempo imposed by pact, and one final condition— until his father passed away from natural causes. In 1479 —after five more years in waiting— Ferran was crowned king of Aragon, king of Valencia and count of Barcelona. This is significant, as it explains that the Catalan-Aragonese states were organised differently. Ferran could not do it all at one sitting. He had to swear the oath in Barcelona, Saragossa and Valencia, to their respective Corts.

You go your way, I’ll go mine

From there on, their hand were full and life was complicated. They became a post-medieval version of “You go your way, I’ll go mine.” Reason of State had not yet been described, but they exercised it fully. Isabel in Toledo —Madrid would not become the capital for another eighty-two years— and Ferran in Barcelona. A separation of states that was effective from the day after the wedding and which would explain, moreover, the absence of descendants of the Catholic couple during those years, at least not Catholically legitimate ones. Ferran was never king of Castile, neither crowned nor considered so. And when he was widowed in 1504, the Castilian court shut their door on him with the solemn expression you Catalan fogey, go to your nation (“viejo catalanote, vete a tu nación”).

Political division of Europe in the late Middle Ages

The cases of Granada and Navarre

Before becoming a widower however, Ferran took care of the conquest of Granada. In 1492, Granada was the last Muslim stronghold in the Peninsula. It occupied the territory that is today the eastern half of Andalusia. It was a focus of culture. An oasis of artistic production. And also a society marked by very acute differences. Granada was incorporated by force. No negotiations, no agreements, no marriages. A military conquest with all its consequences. With the joint forces of the armies of Ferran and Isabel. However, curiously, it was constituted as an autonomous entity integrated into the Castilian State. Ferran had no power over Granada either.

The case of Navarre is not very different. In 1512 Ferran was by then an old widower. He spent his days in Barcelona. But the new queen of Castile —Isabel’s daughter Juana— had been sidelined from the great affairs of State. It was said that she was crazy—untrue. The Castilian nobility, who bore arms, called on him. Ferran was a distant relative of the Navarrese kings and they wanted his presence during the conquest of Navarre to legitimise it. Ferran, who bore the culture of the pact at heart, came forward to lead the Castilian army. Navarre would be Castilian—for his daughter Juana. And in return, no one would oppose his intention of converting one of his illegitimate children into the heir of the Crown of Catalonia and Aragon.

Ferran at the Catalan Parliament or Corts

The case of the Jews and the German bankers

Obviously the pacts were not respected. Navarre was incorporated into Castile in 1516, with a status similar to that of Granada. But Ferran could not found his own dynasty, which would have changed the course of Catalan history. And not so much because of the opposition of the Castilian nobility, but because of the political manoeuvring by the German bankers who administered the fortune of his daughter Juana.

The void left by the expulsion a few years earlier of the Jewish community had been filled by powerful German bankers, the financial courtiers of Flemish king Philip, the queen’s consort. Castile was then an inexhaustible source of resources. Others’. Gold and silver came ceaselessly to Seville from the Americas. And they left for Germany, also ceaselessly. Business has never been keen on ambitious projects. Unstable scenarios, they call them. And the German interests turned the pacts of Navarre into a dead letter.

Who was behind the marriage of the Catholic Monarchs?

This question has always been surrounded by a halo of mystery. We know that Isabel's great rival was her niece—married to a Portuguese king. A priori, everything points to the existence of two opposing centres —Catalonia and Portugal— who rivalled to devour Castile. This explains the chaos and fracture that reigned in Castile. The Aragonese and the Portuguese factions. But the marriages that Ferran arranged for his children revealed the existence of a project that went well beyond a supposed Hispanic union: the old dream of European unification. A project that was eventually wrecked on the European battlefields.

The descendants of the Catholic Monarchs never titled Monarchs of Spain. It would have been abstract and would have been pretentious. The states as they were governed were organised in the Catalan-Aragonese way. It might be illustrated graphically by multiple crowns of different sizes and different materials overlapping —with balances and difficulties that challenged gravity— on the same pate. The first to fuse all the crowns and be named King of Spain was the Bourbon Philip of Anjou, he of the Nueva Planta decrees, in 1715. To achieve this he had to conquer the states of the Crown of Catalonia and Aragon by force. And reduce them to the category of simple provinces of Castile.