Barcelona, December 3rd, 1842. The day that General Baldomero Espartero, Regent of Spain for the underage queen, Isabel II - following the resignation from the role of her mother, Queen Maria Cristina de Bourbon, implicated in a slave trade scandal - ordered the indiscriminate bombing of Barcelona. Twenty days earlier, on November 13th, a spontaneous, popular protest had exploded into an urban revolt. Espartero, who had gone to Barcelona to take charge, resolved the matter in the most direct way possible. And he then uttered a phrase that has gone down in history: “For the good of Spain, Barcelona must be bombarded once every fifty years”. A quote that clearly sets out the nature of the relationship between Spain and Catalonia at critical times - and also at less-critical times. Because Espartero's bombardment of the city was neither the first nor the last. In the last four centuries, the Spanish army and its allies have indiscriminately shelled Barcelona a number of times, brutally fleshing out Espartero's prescription.

The bombardment of 1697

On June 5th, 1697, when the French troops of Louis Joseph de Bourbon, Duke of Vendôme were laying siege to the city of Barcelona, everyone in Paris and Madrid knew that Charles II, the last of the Spanish Habsburg monarchs, was dying without having produced an heir. The gaze of the house of Bourbon in Versailles was squarely focused on the Spanish throne. And, despite the fact that the Barcelona bombardment occurred in the context of an international conflict, the Nine Years' War, which brought Paris and its allies into confrontation with Madrid and its own partners, the action taken by Fernández de Velasco and Hurtado de Mendoza, the Spanish viceroys in Catalonia, was highly suspicious. Their flight from Barcelona, abandoning it to its fate, revealed the extent to which the intrigues of the Bourbon camp in the court of Madrid guided the paths of the conflict and the outcome of the war. Velasco was severely punished for his efforts; revealingly, however, as soon as the first Spanish Bourbon king, Philip V, placed his royal backside on the throne in Madrid, he restored the former viceroy to office.

Siege and bombardment of Barcelona (1697) / Barcelona Historical Archive

Vendôme ordered Barcelona to be bombarded continuously for 62 days, until August 5th, 1697, causing the death of more than 4,000 people. The massacre was of such magnitude that Vendôme, following instructions from Versailles, then swore allegiance to the Catalan Constitutions on behalf of French ruler Louis XIV, basically to avoid precipitating a general uprising around Catalonia.

Engraving of the siege of Barcelona (1697) / Catalan Institute of Cartography

The bombardment of 1713-1714

It was not even fifty years after Vendôme's massacre that his macabre disciples Popoli and Berwick, on behalf of Philip V and Louis XIV, inflicted another bombardment on Barcelona. This time, in the context of the Catalan War (1713-1714), the last phase of the War of Spanish Succession, the Europe-wide conflict centred on the rivalry between Austrian Habsburgs and French Bourbons for the Spanish throne. That bombardment, in which the Catalans, who backed the Habsburgs, were stripped of their national institutions, is one of the best-known chapters in the history of Catalonia. But it is salutary to go over the military details. Between the months of March and April 1713, the powers that supported the Austrian cause gradually withdrew from the conflict in exchange for significant territorial and commercial compensation. The three major institutions of Catalan political power in that era agreed to maintain their resistance till the end, and in response, the Alliance of the Two Crowns - the Bourbon French-Spanish axis - reacted by laying siege to Barcelona.

Bombardment of Barcelona (1713) / Catalonia Historical Archive

For 414 days (from July 25th, 1713 until September 11th, 1714), first the Duke of Popoli - sacked for his incompetence - and later the Duke of Berwick strove to destroy Barcelona, the symbol of Catalan resistance. Throughout those thirteen long months thousands of explosive shells were fired on Barcelona, causing the deaths of an estimated 10% of the population (numerically, around 4,000 fatalities, a figure similar to the 1697 bombardment) and the destruction of all the city’s defences and all the buildings located in the first inner perimeter of the walled city.

Bombardment of Barcelona (1714) / The Army Museum, Paris

The bombardment of 1842

The Barcelona of 1842 was a powder keg of social conflict. The city, still constricted within its walls by the military edict of the Bourbon regime, packed all social strata of society into the same space, confronting each other in a climate of permanent tension that foreshadowed an eventual explosion of violence. And on this occasion, the outbreak of the revolt occurred in the most unexpected way: according to some documentary sources, a group of workers returning to the city after a day beyond the walls, refused to pay the burot, that is, the tax charged for bringing food into the city, on the wine they had brought from their homes for their lunch in the fields. According to other sources, they were just smugglers. But whatever it was, the uprising spread like wildfire, and within hours the working classes of the city had taken up a war footing to reclaim everything from food price controls, to the demolition of the convents and the expulsion of the monks. In that scenario, the republicans, who wanted to send Queen Isabel II to the dustbin of history, managed to put themselves at the helm of the social discontent.

Bombardment of Barcelona (1842) / University of Barcelona

The general captain of the army in Catalonia Antonio van Halen took fright at these events, and withdrew his forces into the refuge of Montjuïc Castle. And that was all that was needed to make the patriotic Espartero spring off his throne into action. The regent of Spain ordered the indiscriminate bombing of the city: 1,014 bombs that cost the lives of thirty people and the destruction of 462 buildings. Then there came a brutal repression: 13 death sentences, 80 prison sentences, reparations of twelve million rals and the dissolution of all worker associations.

Bombardment of Barcelona (1842) / Wikimedia

The bombardments of 1937 and 1938

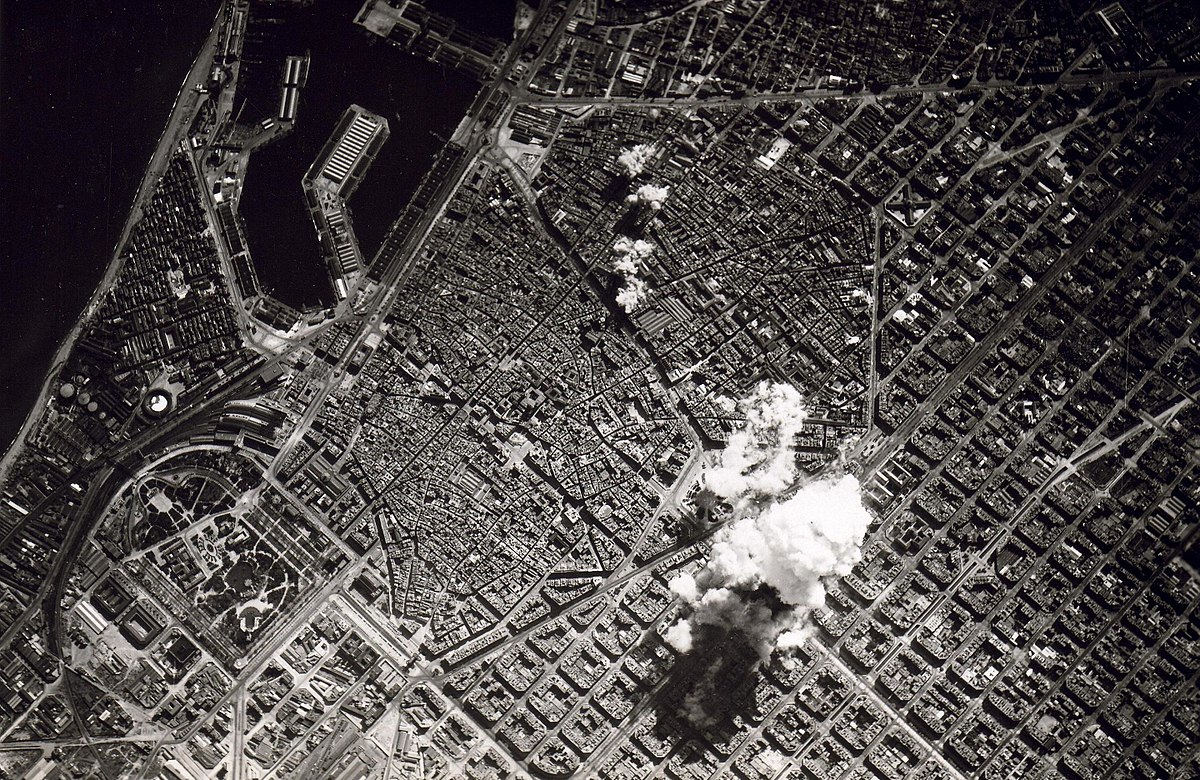

Espartero died in 1879 without having been able to bomb Barcelona again, "for the good of Spain”. It would be Queipo de Llano, one of the leaders of the 1936 Francoist military rebellion, who, almost a century later, would continue the tradition, when he proclaimed: “We will convert Madrid into a garden, Bilbao into a great factory, and Barcelona into a huge empty lot”. The air forces of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy - allies of the Francoist side during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) - bombed civilian targets with great enthusiasm, aiming to undermine the support that broad layers of society gave to the cause of the Spanish Republic. Especially in Catalonia. And upon Barcelona, symbol of the Catalan and Republican resistance - recognised as such even by the Spanish rebel command - the unconditional allies of Franco's "Glorious National Uprising" dropped thousands of bombs. Between February 1937 and January 1939, there were 385 bombardments which caused the death of 2,750 people, serious injuries to more than 7,000 and the destruction of more than 1,800 buildings.

Bombardment of Plaça Sant Felip Neri, Barcelona (1938) / CCMA

Before all these violent events, in between them and, indeed, after them, there have been also been other episodes that are at least as revealing: in 1641 and in 1652, at the beginning and end, respectively, of the Reapers' War; or in 1691, at the beginning of the Nine Years’ War; or in 1705 and 1706, at the beginning of the War of Succession; all with high death tolls. Among so many instances, though, one is especially remarkable: the bombardment that took place on the 16th, 17th, and 18th March, 1938. In just three days, Franco's allies dropped over 44 tonnes of bombs over Barcelona, killing 875 people (757 adults and 118 children).

Main image: Bombardment of Barcelona (March 1938) / Wikipedia