Xavier Gassió was part of the last group of soldiers sent to do their military service in Spanish Sahara, Spain's last colony. He was there when events accelerated: when the Spanish promised the territory self-determination, when the king of Morocco organised the Green March, when the agreements were signed in Madrid meaning the cession of the territory to Morocco and Mauritania, when Franco died and when the Moroccans occupied El Aaiún (لعيون), the territory's capital. Now, 40 years later, Gassió is publishing Sáhara español. El último reemplazo (Arzalia Ediciones, literally "Spanish Sahara. The last reinforcements), a book whose text and images remember that convulsive year during his youth. A book in which Gassió discusses what the youths' military service meant, in that colony forgotten in the middle of the desert, and how Spain left the territory.

A picture's worth...

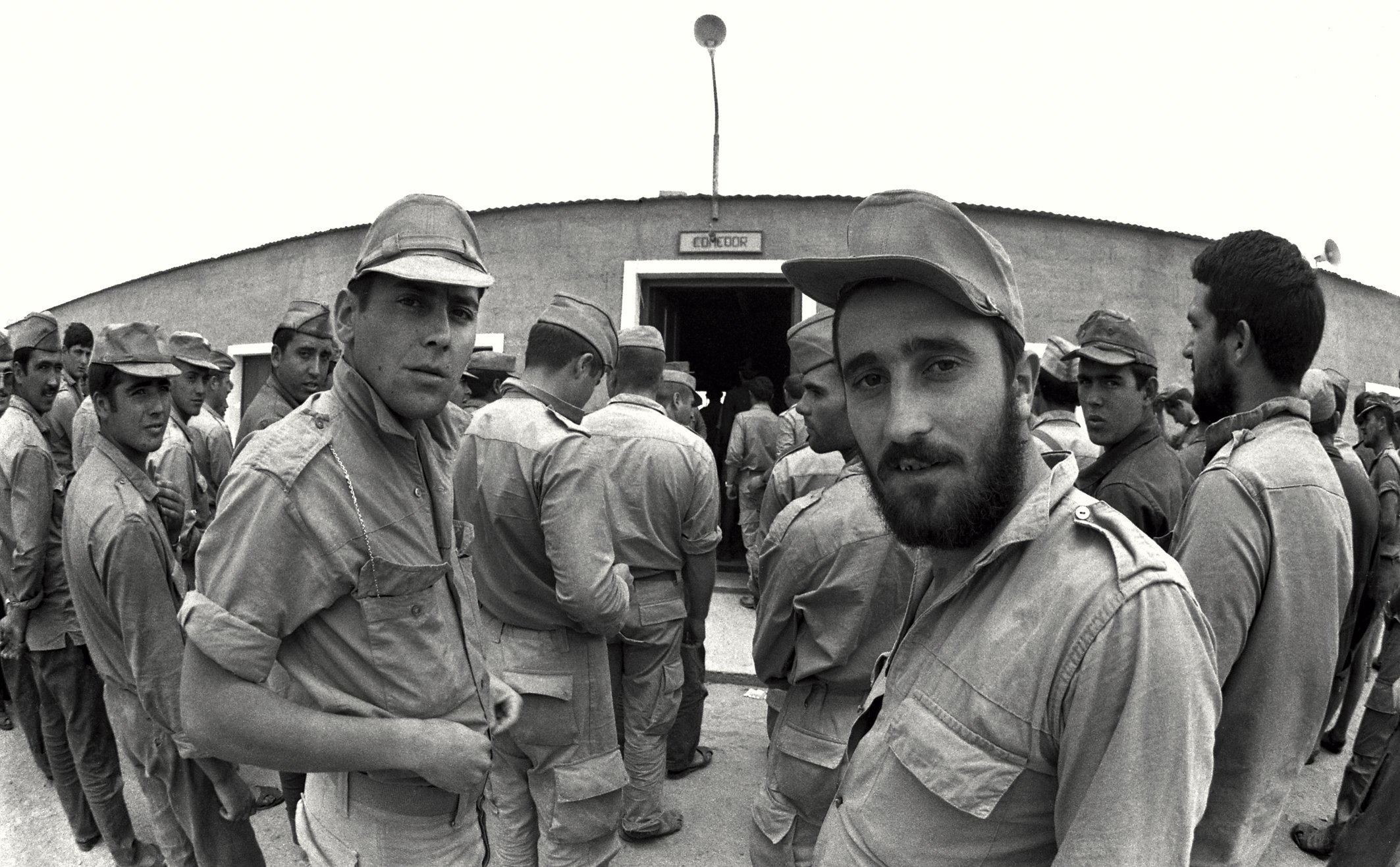

If a picture's worth a thousand words, Gassió's book must be getting on for worth a million, as it includes an impressive collection of photographs. During his military services, Gassió moonlighted as a translator of the manuals of the cameras his comrades bought (the territory was free from taxes and recruits often took some machine or other with them on their return to the Iberian Peninsula); in exchange for the translation, he asked to be able to use the camera for a while. In this way he compiled a spectacular collection of photos: of his comrades, of the facilities, of the Saharans, of the souvenirs, of El Aaiún, of the landscape, of the weapons... He became something of a visual notary, documenting in detail the last months of the colonisation of the Sahara. Gassió, who later became a press photographer, had a natural instinct to document things that are important and illustrative. Few people would have thought of photographing a military locker, that tiny space which so well reflected the spirit of military service: Gassió did so and shows it in his book; an image that strikingly illustrates what the life of so many Spaniards was for a year or more... But Gassió also documented the pornographic shows of the Sahara, the travelling artisan salespeople, the tanks, the Saharan demonstrations, the camels, the filthiness of the streets of El Aaiún...

At its heart, military life

Gassió's book isn't exempt from a certain nostalgia. Although the author clearly presents himself as being anti-military and reveals all the miseries of the Franco-era army, he has certain positive memories of military life, especially for what the camaraderie between people from different backgrounds and social classes meant. Gassió, despite harshly criticising some aspects of military life, keeps adding details of their shared experiences, their military camaraderie. In fact, the Saharans appear very sporadically in the story, because the military society lived apart from them (with the exception of those destined for the tropas nómadas auxiliary regiment or the territorial police). It's important that the author himself explains that, for the soldiers, it was "forbidden or inadvisable" to go through the area of jaimas, the local tents, next to their barracks. At another point, Gassió explains that a visit to a metalsmith constituted "an excuse to hold a conversation, between teas, with a Saharan". Gassió lived in the Sahara, but didn't live among the Saharans. But, with much sincerity, he doesn't try to lie about it.

Colonialist without collusion

Gassió was sent to the Sahara to help keep the territory a Spanish colony. He followed the orders he was given but, despite everything, his book is in no case an apology for Spanish colonisation (unlike many of the books by other soldiers sent to the territory). The images of the poverty of the Saharan neighbourhoods are proof of the deficiencies of Spanish colonialism, and disconstruct the propaganda about the goodness of the Spanish occupation offered by the Franco regime. In reality, Gassió's photographs show us the tension between the Spaniards and the Saharans, forgotten since the Moroccan invasion. Gassió doesn't hesitate to include photos of the city's graffiti, showing the patriotic wave seen in the Sahara before the Polisario Front, the independence movement. The soldiers filled the houses of El Aaiún with slogans praising Franco and Spain and wishing death on the Polisario. And it didn't stop at graffiti: in one picture you can clearly see the fences set up to isolate the Moroccans within their neighbourhoods, a true Spanish apartheid. Gassió even prints some images which he didn't take showing the torture inflicted on those suspected of sympathising with the Polisario in Spanish military facilities. Images which make very clear the terrible aggression of the Spanish colonialist forces. The brutalities of the Moroccans in the Sahara cannot serve to wipe clean the memory of Spanish colonialism and idealise the Spanish presence in that piece of desert.

To leave and to condemn

We should be grateful for Gassió's position. Some of the photographer's companions in arms have written books with autobiographical elements which are terribly critical of Moroccan colonialism, but extremely lenient towards Spanish colonialism. In fact, part of the pro-Polisario movement is still marked by a clear emotional neo-colonialism. Despite everything, Gassió, who makes no detailed analysis of what Spanish colonialism meant, does dedicate a good part of the volume to analysing the ceding of the colony to Morocco. Whilst the meat of the book is based mainly on his personal experiences, the final part is based, primarily, on other sources: diaries, books... And in this section Gassió unreservedly condemns the handing over of the territory to Morocco, against the wishes of its inhabitants.

40 years

Gassió's photographic and written record allows for a new assessment of another of the great pending subjects of the Spanish transition to democracy. At the same time that it buried Francoism as fast as possible, without even giving the dead proper burials, the young Spanish democracy rushed to archive in some corner the memories of colonialism to slowly be covered in dust. Whilst the Saharans were submitted to Moroccan domination, Spain hastened to distance itself from its colonial experience, as if it had never existed. Gassió contributes, fortunately, to bringing it to light.