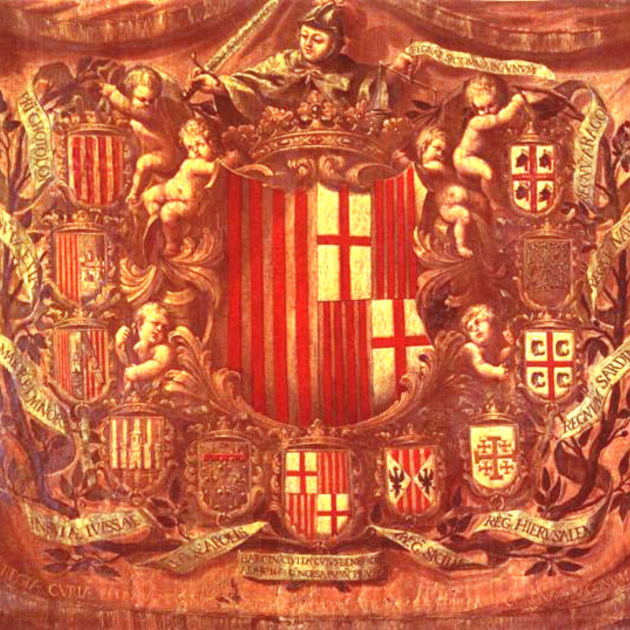

The place: Lleida; the time: one day in August 1150. 871 years ago. The occasion: the celebration of the marriage between Ramon Berenguer IV, independent count of Barcelona and authority-holding Potestas of Aragon, and Peronella, daughter and heiress of king Ramir of Aragon. That ceremony sealed the dynastic union between the two domains, which would last for more than five centuries (until 1714) and which, in the course of its existence, would incorporate up to six different territories (Mallorca, Valencia, Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, and Naples). For centuries, this conglomerate was called simply the "Crown"; until Ferdinand the Catholic (in the late 1400s) added "Aragon". But did this denomination accurately describe the weighting of power within the conglomerate? And is it right to continue using it today?

Modern representation of Ramon Berenguer IV and Peronella (16th century) / Source: Arxiu d'ElNacional.cat

Is it Aragon that swallows Barcelona, or Barcelona that swallows Aragon?

Spanish historiography has traditionally placed great emphasis on the prominence of king Ramir. But modern research reveals the opposite. When negotiations began (1137), the small kingdom of Aragon was mired in the deepest crisis of its short existence. The country was immersed in a climate of civil war, with local power divided between supporters and detractors of the will left by Alfonso I - Ramir's predecessor - who had bequeathed the kingdom to the military orders. He had lived under the threat of the expansive ambitions of the Navarrese and Castilians, who were plotting to reap the benefits of this crisis. In fact, the Castilians had already entered Zaragoza, and the Navarrese were at the gates of Jaca. In that context, the marriage was the real lifeline that would prevent the wreck of Ramir's oligarchic grouping and the disappearance of the Aragonese kingdom.

The Bel·lònides, Catalan or Aragonese?

As a result of these negotiations, Ramir handed over his power (that is, the potestas) to his son-in-law, Ramon Berenguer. Revealingly, even before the wedding. But the most important thing was that it was the Bel·lònides, the Catalan lineage founded by the Carolingian count Guifré el Pilós at the end of the ninth century and not the Ximeno, Navarrese-Aragonese, who became the new rulers of that conglomerate. This element is of decisive importance, because in that context, states (as they are currently articulated) did not yet exist. Rather, sovereigns (regardless of their rank or dignity) had a patrimonial idea of the office and dominion they exercised over people and land. And if we add the patriarchal ideology that prevailed everywhere, we can say that, from 1150, the small kingdom of Aragon became a domain - a property - of the Catalan lineage of Ramon Berenguer.

The Carolingian Bel·lònides, minor branch of the imperial family / Source: Rotllo de Poblet

The four-bar flag, Catalan or Aragonese?

Spanish historiography has insisted to the point of exhaustion on the Aragonese origin of the flag with the four red bars. But archaeological research has shown otherwise. The tomb of Ermessenda of Carcassonne, independent countess of Barcelona, was painted with the so-called "bars of blood". Ermessenda died in 1058; half a century before Pere of Aragon (1094-1104), the so-called pioneer. Probably, when the wedding in Lleida was celebrated, the "bars of blood" were already the standard of the two houses (the Bel·lònides and the Ximeno). But its use began in Barcelona, long before the dynastic union with Aragon. And its universalization - in all the territories of the Crown - did not come about with the marriage of Ramon Berenguer and Peronella; but almost a century later, in the time of Jaume I, the 15th Bel·lònida (1213-1276).

Expansive enterprises, Catalan or Aragonese?

The subordinate position of Aragon with respect to Barcelona, from the beginning of the negotiations, would mark the power relationship during the centuries for which that conglomerate existed. Whether it held two territories or six. Peninsular (the Valencia country) or maritime (Mallorca, Djerba, Malta, Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, Naples), the expansion was driven by a strong alliance formed by the Catalan military establishment (the feudal nobility) and the powerful Catalan mercantile classes (especially those of Barcelona, and to a lesser extent those of Valencia and Palma). It was the Catalan elites (or those of “the Catalan nation” in the case of Valencians and Mallorcans), and not the equivalents from Aragonese society, who contributed the human and material resources of these ventures; with a common goal: to expand the patrimonial dominion of the Bel·lònides and the Catalan feudal barons; and expand the business of the Catalan merchants.

Catalan Atlas, created by Abraham Cresques (1375) / Source: Museu d'Història de Catalunya

The Almogavars, Catalans or Aragonese?

The Chronicle of Bernat Desclot (1288) says that admiral Roger de Llúria, after the successful Sicilian campaign (1285-1288), proclaimed that "no fish should rise above the sea, unless it bears a shield or sign of the king of Aragon in the coha”. This might suggest that those Almogavars soldiers did not identify as Catalans, but as Aragonese. At least, as subjects of an Aragonese king. However, most documents of the time show the opposite. The Almogavar captain Ramon Muntaner, who had also been in the Sicilian campaign, wrote in his Chronicle (1325) that "With Murcia I must hurry, all populated with Catalans, and likewise Elx, and Oriola, Alacant and Guardamar, Cartagena and elsewhere (...) are Catalan verses and speak beautiful Catalan of the world; and they are all good with arms and with all good deeds."

Representation of the Almogàvers / Source: Museum of the History of Catalonia

The Consulates of the Sea, Catalan or Aragonese?

The economic strength of Barcelona, and by extension that of the Principality of Catalonia - and we can say of the Crown as a whole - rested on its maritime trade. The documentation of the time reveals that the manufacturing and mercantile activity, alone, of the Catalan capital, far exceeded the total of the kingdom of Aragon. From the 13th century, Barcelona was governed as a municipal republic; clear proof of its economic power. And it competed with the republics of Venice and Genoa for the commercial (and even military!) domination of the Mediterranean: the celebrated alliance of the count's power and mercantile classes. The Consulates of the Sea, scattered throughout the Mediterranean, would be the culmination of that enterprise. They would not only act as spaces of representation, commerce and sovereignty - that were Catalan, not Aragonese - but they would also create international maritime law.

The Katalanit, Catalans or Aragonese?

Other documents from the medieval period (Venetian, Genovese, Byzantine, and Arab) refer to the merchants and soldiers of the Crown, exclusively, as catalani. However, the denomination aragoni or aragonese does not appear until after Ferdinand the Catholic (late fifteenth century). Even the Jewish Diaspora of 1492 (which originated in all of the territories of the Crown) calls itself "Catalan". And yet, the case of Baruj Almosnino, a rabbi of the Judeo-Catalan community in Thessaloniki and a descendant of a Jewish lineage from Jaca, is very revealing; that in the documentation of the time (16th century) he identifies himself and the community he represents as Katalanit, clearly differentiated from the Sephardim of Castilian-Leonese origin. Nowhere is there found anything related to the kingdom of Aragon or the Crown of Aragon, invented by the Catholic monarch.

Book of the Consulate of the Sea / Source: Arxiu Historic de Barcelona

Can we refer to the Catalan Crown?

Some current Catalan historians reject this nomeclature. They claim that the sovereigns of Catalonia never wore a crown. And that is true. And it is also true that in medieval ideology, it was proclaimed that kings were kings by divine intervention, that is, that they sat on the throne because God had decided they would. And that, on the other hand, in Catalonia it was proclaimed that the prince - that is, the principal man - was appointed not because God had decided it, but by virtue of an earthly covenant with the political institutions of the country. However, we must not forget that that Crown, for practically the entire medieval period, possessed a Catalan lineage. And that this lineage, the Bel·lònides, always ruled its domains - its properties - from Catalonia. If we can’t call it the Catalan Crown, then what can we call it?