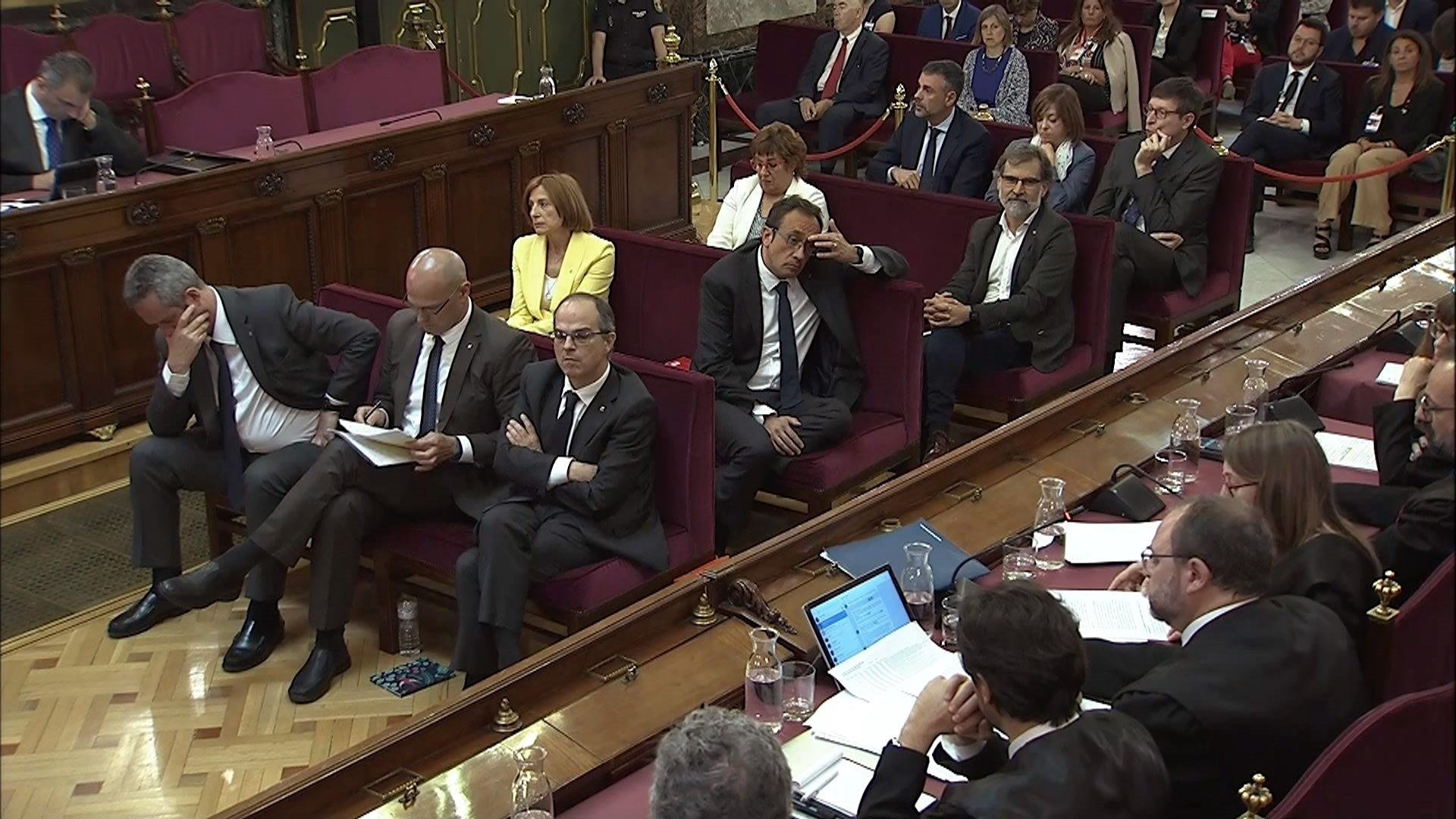

This October 14th marks a year since the Spanish Supreme Court handed down its verdicts on the Catalan pro-independence leaders, tried over the events of the 1st October referendum and the Catalan independence process. The charge of rebellion failed, but the court clung to the alternative accusation of sedition to uphold the prosecution's narrative and justify the pre-trial detention that had been imposed on the six Catalan government ministers, the speaker of the Catalan Parliament and the civil group leaders Jordi Sànchez and Jordi Cuixart from the very day they were first declared to be under investigation.

The verdicts and sentences, which were leaked hours before they were made public, sentenced the nine imprisoned leaders to 9 to 13 years in prison. Oriol Junqueras is serving 13 years in jail. Ministers Raül Romeva, Jordi Turull and Dolors Bassa, 12. House speaker Carme Forcadell, 11 and a half. Joaquim Forn and Josep Rull, 10 and a half years. And the two civil society activists, Jordi Sànchez and Jordi Cuixart, 9 years each. The criminal chamber of the Supreme Court, presided over by judge Manuel Marchena, said that the three defendants who were at large throughout the trial, Carles Mundó, Meritxell Borràs and Santi Vila, were not guilty of misusing public funds, but were guilty of disobedience, for which they were heavily fined. To justify the sedition charges, the judges supported one of the prosecution's arguments: that in the autumn of 2017 there was a "public and tumultuous uprising" in Catalonia.

The seven male Catalan political prisoners who are in Lledoners jail, Catalonia. From left: Jordi Sànchez, Oriol Junqueras, Jordi Turull, Quim Forn, Jordi Cuixart, Josep Rull and Raül Romeva.

Ever since the prisoners entered pre-trial detention close to three years ago, their lawyers have fought constantly for their release from custody via a range of legal avenues. In addition to the appeals to overturn the verdicts and sentences and the legal demands for them to be allowed out of prison, their lawyers have also presented submissions to try and obtain prison leave permission as well as the 3rd level or "open prison regime" status under which they would only have to return to the penitentiary to sleep. But both the effects of Covid-19 on the prisons, and then the judicial counterattack against the leave privileges they had been granted, meant that the Catalan leaders are again on the back foot. The two female prisoners, Carme Forcadell and Dolors Bassa, are the only ones who are still permitted the open regime now. The rest are locked up under a strict regime due to health protocols, with almost all the leave rights they briefly enjoyed now suspended.

In this context, what are the immediate prospects for the Catalan political prisoners? When will they be able to get out of jail?

"It's totally uncertain," says Andreu Van den Eynde, lawyer for Oriol Junqueras and Raül Romeva. “If the law were strictly adhered to they should be out,” he adds.

The three ways to get out of prison

When they were convicted there seemed two possible routes to gain an early release: a pardon and an amnesty. But the third, longer, route is Europe. And it is the one that the defence lawyers see as most feasible right now. "An international appeal is what I see as most likely to succeed," says Van den Eynde, who recalls that "whenever an international jurisdiction has analyzed our case, it has found in our favour." But for this to happen, the Spanish Constitutional Court must first resolve the appeals it has before it. And here, we re-enter an area of uncertainty. The periods of time necessary are also unclear. “The Constitutional Court can move fast on issues relevant to its own renewal and it may surprise us,” Junqueras’ lawyer says, but he's not betting a lot on it. This a court which can leave a case sitting unresolved for up to two years. The main problem is that none of the legal deadlines and assumptions are being met in this matter which is approached as a political case. "It's unpredictable. It can change overnight," says Andreu Van den Eynde.

Oriol Junqueras and Raül Romeva on prison leave under the "open" regime they were briefly permitted. / Maria Contreras

The other possibilities depend on the will of the Spanish government: a pardon - under which the Spanish executive could revoke the sentences imposed, while not wiping their convictions - or an amnesty - which would require a special law to be passed and therefore a Spanish parliamentary majority in favour of it. The lawyers opt for an amnesty as a preferable solution, but right now they do not see as viable. There is in fact a further option, also dependent on the Spanish government, which is the reform of the Penal Code to rewrite the controversial offence of sedition under which the nine prisoners were jailed.

Both the reform of the Penal Code and the amnesty law are based on legislative initiatives that could have more future than pardons. And out of the two, the PSOE, senior partner in the Spanish government, seems to opt more for the reform of the Penal Code and the offence of sedition. But right now there is nothing on the table. No proposal to amend the Code, nor any draft amnesty law. Nothing.

Pardons follow an uncertain path, too. It is the option that political prisoners like least, but right now it is the only one that has begun to "walk". Requests to pardon the prisoners have been presented by third parties and thus must be legally evaluated by the Spanish government and, if it comes to it, validated by the king.

Leave prison only to return

During this last year since the verdicts were announced, the political prisoners have asked for all the prison leave permits that the prison system guaranteed them. And despite being granted time outside the jail, it has turned into a year of exits and entrances. Of small steps forwards followed by major setbacks, in terms of their rights and their release.

After the prisoners' sentencing last year, prison authorities granted them a standard second level prison regime and they then began to present requests for leave to take up a job or do volunteer work outside the jail. They also started being granted permits to spend weekends at home. The provision for work leave under article 100.2 of the prison regulations is a halfway point to being granted an open regime, and this latter status was awarded to the nine in early 2020. At human level, it was a key step in the efforts to rebuild their lives - although not their political careers, as their convictions still disqualify them from holding public office.

Carme Forcadell at the commemoration of the 40th anniversary of the Catalan Parliament / Sergi Alcàzar

But right now, the open regime has been suspended for the seven male prisoners while the Supreme Court considers decides whether to repeal it, after an initiative by judges and prosecutors enabled the Supreme Court to make new doctrine granting itself the final word on how the Catalan prisoners must serve their sentence. Carme Forcadell and Dolors Bassa are affected differently: they will also be subjected to the Supreme Court's final ruling, but for the moment, a judge with a different point of view has decided that until the high court decides, the two prisoners may continue with the usual regime of leaving the prison during the day and returning at night.

Covid-19 also ended up complicating the situation for the Catalan prisoners still further. While prison authorities were extending open regimes during the pandemic, the pro-independence leaders first had their leave rights suspended and then were subject to strict protocols of isolation after the few leave intervals they were still able to benefit from outside the centre. This led to 22-hour internments in cells to prevent possible contagion once they returned to prison during the escalation phase of the confinement.