Vicenç Villatoro is a journalist and writer, but in his latest editorial work he has been more of a confessor, psychoanalyst and a notary, listening for hours to Jordi Pujol, the 126th president of the Generalitat of Catalonia, who at the age of 90 was in need of making a will - a political will, of course. Pujol, who had been shut away in self-imposed ostracism, has decided to raise his head: first, to apologize to Catalans, but, above all, above absolutely everything else, to vindicate his political legacy, his work of government, which he himself considers much more important and transcendent than his “sin”.

"I am not a corrupt person," says Pujol categorically, "I feel guilty for a mistake I made due to a lack of reflection, due to negligence and to weakness, but it is just that my life be judged looking at both sides of the ledger."

Pujol's confessions have been collected by Villatoro in a book that adopts an interview format, entitled Entre el dolor i l'esperança ("Between pain and hope") (Edicions Proa), which was presented this Wednesday by Josep Ramoneda and Villatoro himself, but without the presence of Pujol, who preferred to explain himself in a video.

"Perfection does not exist"

The former Catalan president maintains his own version of the events that have impacted frontally on the extraordinary figure who dominated Catalan politics for 20 years. He only blames himself for never having regularized the savings he held in Andorra with the Spanish Treasury, and is of the view that it should be considered a minor matter compared to the magnitude of his political work. “The bequest was from my father, the money did not come from any bribe, nor was it related to politics, it was money that I did not use, nor did I spend... There were things that I had to do because Treasury required it, but I thought ‘I’ll do it tomorrow’, and that tomorrow never came. Anyone can be assailed by error or weakness", he says to excuse himself, and compares his political biography with a beautiful Renaissance tapestry that is marred by a small tear, an irrecoverable error, a human error," which can be forgiven, because it is a human error and perfection does not exist or is very difficult”.

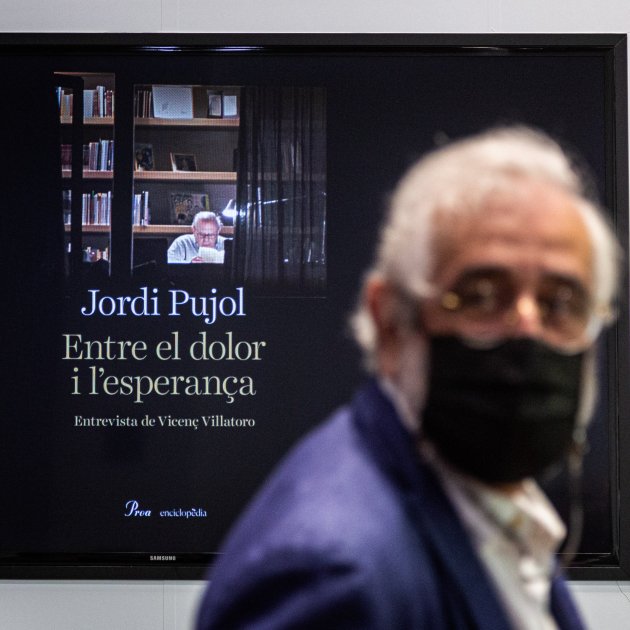

Vicenç Villatoro at the presentation of the book Jordi Pujol. Entre el dolor i l'esperança / Montse Giralt

In the end, the text as a whole shows, on the one hand, Pujol's pride in the work he did, and on the other, his anger at being disgraced and what he considers "systematic action of demolition" against his person, to which, he says, he has been subjected "out of envy or a desire for revenge." Pujol is so convinced of the value of his political legacy and the injustice with which he is judged that he has no problem comparing his fate with that of German chancellor Helmut Kohl, “one of the most important, most positive and most successful German politicians of the twentieth century... The chancellor of the reunification who played a decisive role in the introduction of the euro, but who at the end of his political life was forced to resign as chancellor and abandon all his positions in the party, by an illegal financing scandal”.

Vicenç Villatoro at the presentation of the book Jordi Pujol. Entre el dolor i l'esperança / Montse Giralt

In this regard, Pujol says that he is “ready to cope with imprisonment, ruin or death, but not for public disgrace and shame, not for ferocious criticism that is neither just nor responsive to reality, and, to a large extent, is a settling of scores”.

The pardon

Because, in spite of everything, Pujol continues to defend his ethical, moral and religious principles - “I am from the school of [Charles] Péguy!” - he rejects greed, but defends the greatness of politics "when power is put at the service of a project that goes beyond the person himself, with generosity, passion for the common good, altruism..." And indeed, "the fact that I have preached and have constantly put an emphasis on leading by example makes my case more serious and therefore more painful." "It is for that reason that yes, I apologize, which is not quite an indulgence to anyone who wishes to punish me. I do apologize to those close to me... and I also apologize to the young man I was and to my country, to the people of my country."

The book, as Vicenç Villatoro has noted, does not only address current issues, but goes well beyond. There are references to the past and the future, and an analysis of the present in different contexts: Catalan, Spanish, European and global.

Those who want to look for controversy will find it. Pujol has made a political will and makes it clear that he has never been pro-independence. He defends Spain's Transition and acknowledges the role of the monarchy in consolidating democracy, which these days may cause blood to boil for some. If anything, he regrets that the successes of the recent past are being damaged now.

Pujol also takes advantage of the opportunity to go into some controversial aspects of his biography. For example, he flatly denies ever giving up the economic concert when the first Catalan Statute of Autonomy was debated. And he remembers the "own goal" that the second one meant, although he attributes it to an offensive by the Spanish deep state.

In any case, it is clear, as Villatoro says, that "without Pujol we cannot explain the Spain and Catalonia of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st".

Main image: Vicenç Villatoro in the presentation of the book Jordi Pujol. Entre el dolor i l'esperança / Montse Giralt