"Prison doesn't teach anything, it just locks you in," says Òmnium Cultural president Jordi Cuixart. But in prison there is time. And time goes slowly. In the case of Cuixart it was three years, eight months and seven days, which he invested in reading, in getting to know a part of the human universe that was shut inside the walls of Soto del Real and Lledoners, in waiting for fortnightly conjugal visits, in learning pottery... and in writing a diary. The result of those written reflections, which he began to collect in a notebook he found in his cell in the Madrid prison of Soto, have given rise to a book that has just reached the bookstores, under the title Aprenentatges i una proposta ("Things learnt, and a proposal").

The proposal announced by the title is summed up in the call for a new referendum, without adjectives and as soon as possible. It is not a call he is making to the political parties, but to society. But also, as he admits, clearly to place pressure on the political groups. "We need to govern Catalonia well and, at the same time, commit ourselves to holding a new referendum very soon and without adjectives. Whether the state likes it or not. This is what 'We'll do it again' is: voting as many times as necessary", he asserts.

The Catalan pro-independence leader, who maintains that the only limit to this movement must be non-violence and that no democratic path must be abandoned, warns that a referendum without adjectives could bring together the whole of the independence movement, just as it became the great consensus in the meetings of the political prisoners in Lledoners.

Critical of the parties

Cuixart does not hide his reproches of the parties. Even his irritation with them. "When we talk about political parties, we must always keep in mind that they have a certain tendency to use lynch tactics. When elections are approaching, especially (and even legitimately), but as well, when they haven't got such a clear excuse,” he says. And yet he insists on Òmnium's will not to fall into the trap of being 'anti-party'.

The activist explains that he immersed himself in reading, from Sophocles' Antigone, to Hannah Arendt, to Thoreau, Gramsci, Luther King, Gandhi, Mandela, Rosa Luxemburg, Václav Havel, Rodoreda, Joan Sales and so many others that he lists and quotes in the work. Between his battles to get a reading lamp to read in the icy, dark prison of Soto, and struck by the inexplicable dirt of that prison, the Òmnium leader concluded right there that the Spanish state had crossed a red line. And the independence movement had, too. Because, in reality, prison was not a limit for the activists and leaders, rather, it was evidence of the most important weakness of the state.

Not afraid of prison

"They should not threaten us with prison anymore, now we know what it is. And we, too, have lost our fear and we will make use of it to educate ourselves and acquire even more knowledge, to come out even stronger, to be more useful, to be more sensitive and more decisive", he warns. In fact, this is one of the key conclusions of the book, and it is expressed from the Catalan prison of Lledoners in the form of a warning: "If we are not clear that [our] imprisonment cannot be a limit to [everyone's] exercise of fundamental rights, it will be impossible for us to move forward."

Cuixart celebrates the referendum of 1st October, 2017, as the greatest act of civil disobedience in recent decades in Europe, and the general strike two days later as an act of collective dignity that "forced the king of Spain to get up out of his throne because he saw that Catalonia was leaving". But he also does not hide his criticism of what went wrong on October 27th after the proclamation of the republic. “When you don’t know which port you’re heading for, no wind blows in your favour,” he warns, quoting Seneca.

The power of the movement

Next to these uncertainties, Cuixart places the certainty of the strength of the independence movement on the street. The Òmnium president does not hide his criticism of the Catalan institutions that did not know how to react to the sentence of October 2019 - "it seems to me that now we can say clearly that the response from the institutions was nowhere near the gravity of the occasion"- or a Catalan government that forced them, in Lledoners, to fill out forms on the prison treatment programme -" didn't we have a government that recognized us as political prisoners?" he asks. But on the other hand, he never tires of emphasizing the strength that the support of the people represents. "Possibly we are not aware of our power," he advises while pointing out, "Possibly we need to show much more than we have shown so far."

Cuixart turns to Hannah Arendt to differentiate between force and power and concludes that, in Catalonia, the state has the force of the police, the army, the courts, the Ibex companies and so much of the media, but has lost the power which arises from the people gathered together to achieve a goal. Nevertheless, he admits that Catalan society, despite accumulating unusual power, "has not been able to translate it into force".

Personal impact

As the pages of the book progress, political reflections are intertwined with the personal experiences of those three years and eight months. The family, the support from Òmnium, the discomfort at the memory of his first exculpatory statement and the change of strategy in the Supreme Court - "the premise was clear: the goal is not to leave soon, it is to leave well" - which ends with his proclamation of "We'll do it again" before the court presided over by Manuel Marchena, in the same courtroom in which Catalan president Companys was put on trial in 1935.

The diary does not follow a chronology, but jumps back and forth, reconstructing scenes and moments: the first brutal impact of prison; the emotion of the birth of his youngest son, Camí, and the battle to be able to be present at his birth; the surgery he underwent at Manresa Hospital and the moving warmth with which the operating team welcomed him - also wearing yellow surgical hats for the occasion; and the moment when the news broke that his prison leave had been revoked, while he was sharing a meal with his family in a public place - and when he left he received the greetings and applause of those who were at the other tables...

From the tears expressing the impact of finding himself locked up and the decision to continue with his plans for the family despite being in jail, to the support of cellmates and his outrage at the treatment given by some prison officers. The surprise in discovering the people he happened to be with and in discovering himself. All this because in prison, nothing is learned, but, as he confesses in the last pages with a note from the diary from November 20th, 2017: "Going through prison turns everything upside down."

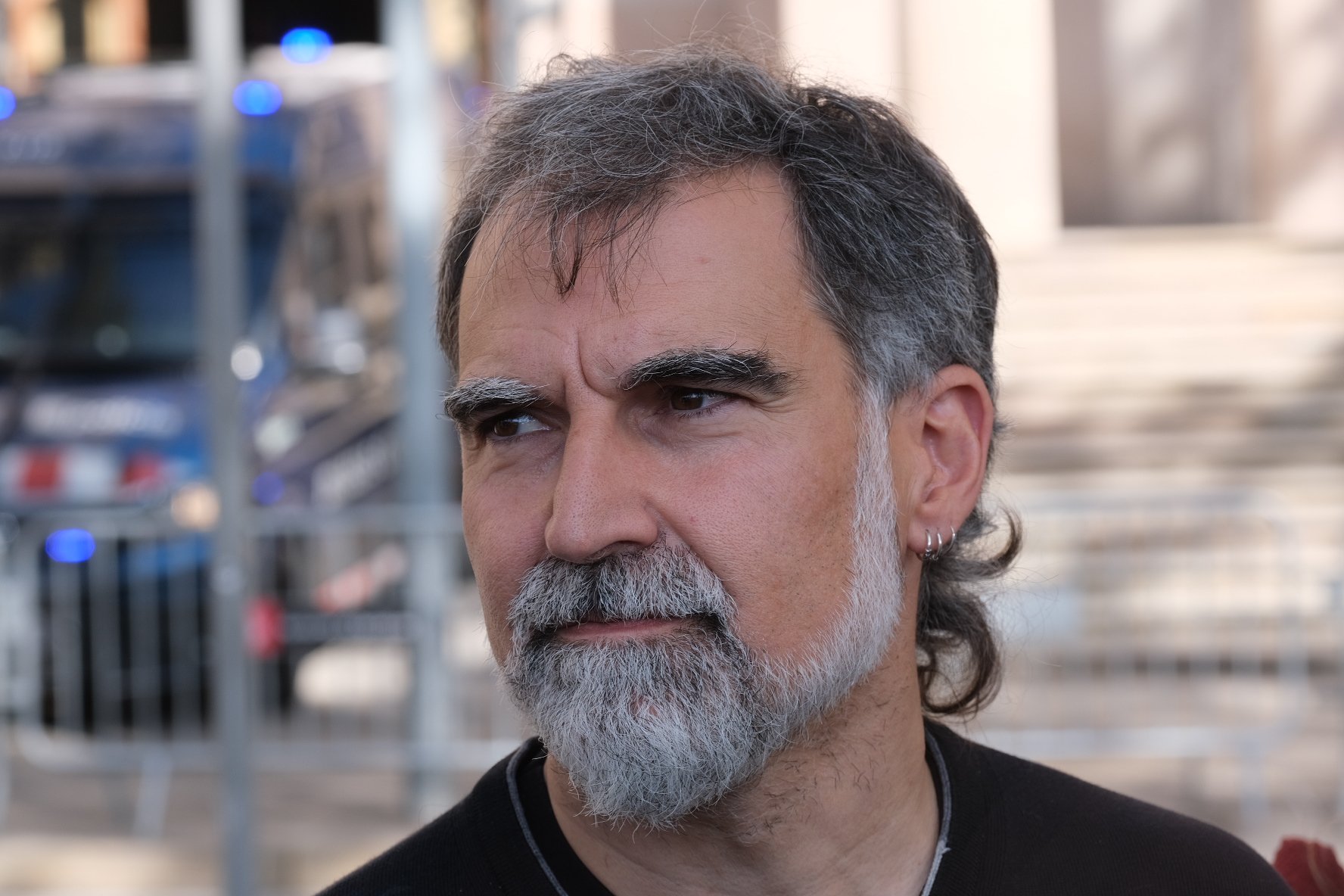

In the main image, Òmnium Cultural president Jordi Cuixart / Carlos Baglietto