Time goes by, but the image remains unchanged. Five years ago, three Catalan deputies, Jordi Turull (CiU), Marta Rovira (ERC) and Joan Herrera (ICV) landed in Madrid on a mission from the Parliament of Catalonia: to argue the case for a negotiated referendum on Catalan independence before Spain's Congress of Deputies. Specifically, they were requesting the transfer to Catalonia of the competencies, currently held by the government of the Spanish state, to be able to call a self-determination consultation, by means of an amendment to an article of the Constitution. The result was as expected: 47 votes in favour, 299 against and one abstention. Today Turull is in Lledoners prison; Rovira, in exile in Geneva; and Herrera, has abandoned politics for a role in a state corporation. It was not the first nor the last attempt to reach agreement on a Catalan referendum in the Spanish capital. The list, in fact, is long.

Indeed, without looking any further afield, the most recent attempt has been made in the last few days. The speaker of the Catalan Parliament, Roger Torrent, fronted up in Madrid last Thursday to make a political address. At the Hotel Palace, just metres from the Congress of Deputies, he explicitly renounced the unilateral route to independence - "the unilateral path is not for anyone who wants to take it, but rather for those who are able to take it" - and he waved the flag of dialogue. And in this context, he put his proposal on the table: taking a leaf from the Canadian debate on Quebec's self-determination, he called for a "clarity pact", that would "reach agreement on when, how and under what circumstances we will celebrate the referendum that will put an end to the conflict". The Catalan Republican Left (ERC) politician received the same clear and forceful answer as his predecessors had done: no.

Just a couple of hours later, the person in charge of pulling up the castle drawbridge was Spain's outgoing foreign minister, Josep Borrell, showing off his diplomatic skills once again. "I don't know how many times the prime minister has to repeat that there is no constitutional possibility of holding a referendum for secession in Catalonia," he asserted with a sarcastic smile. "Mr Torra and all those who every day claim the right to self-determination must be aware that there is nothing in international law that supports this demand," he reiterated. And he denied that Quebec was an example of an agreed referendum, because its two consultations had been unilateral.

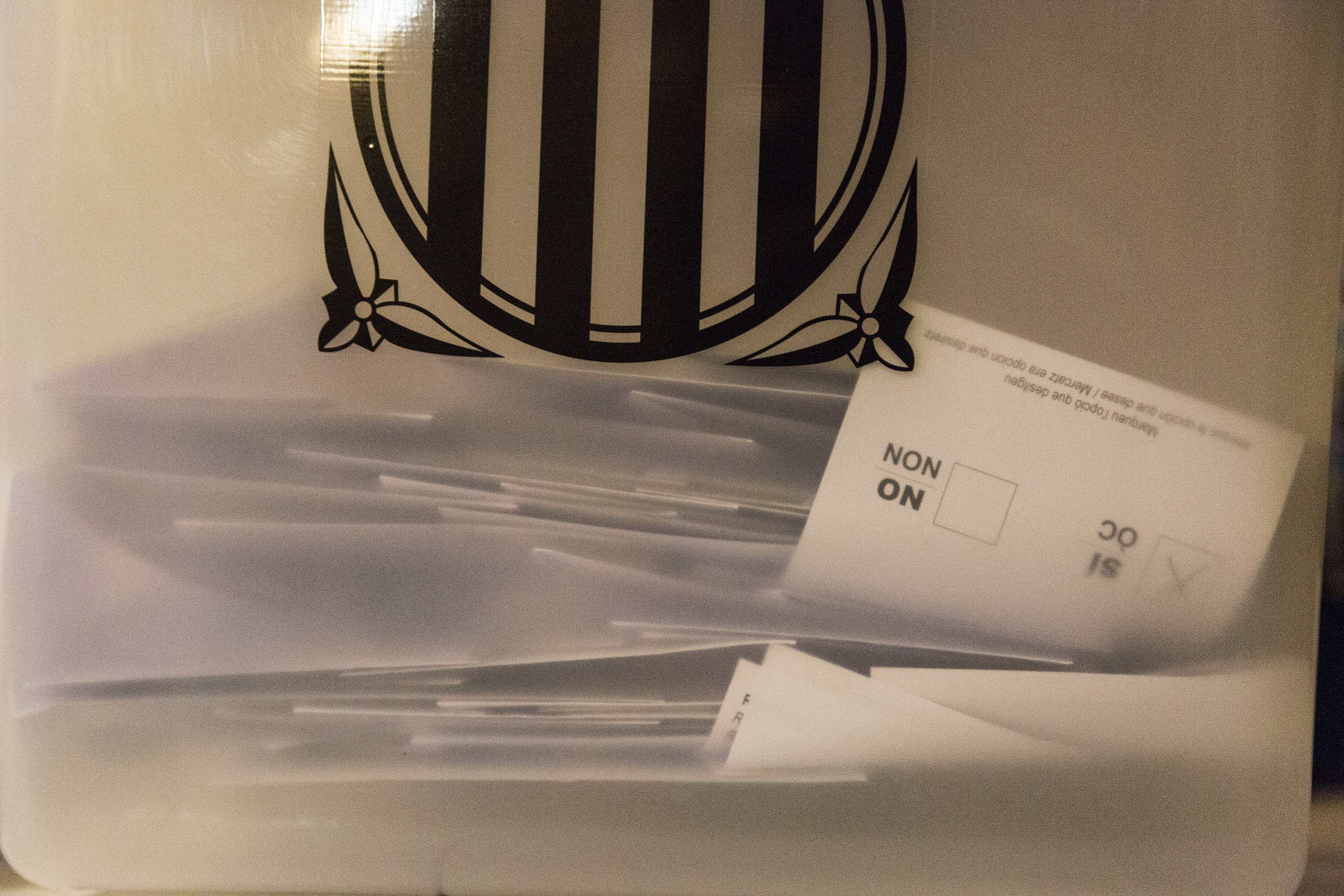

It is true that the two Quebec referendums, in 1980 and 1995, were held without any prior agreement with the federal government, whose only intervention was to assure that, whatever the outcome, it would not be binding. In spite of this, and after the narrow victory of 'no' voters by 55,000 votes in the second poll, Ottawa went to the country's Supreme Court to ask if Quebec had a right to declare its independence unilaterally. The answer came in August 1998 and it was a 'no'. But the court's ruling also established that the government of Canada should enter into negotiations with its Quebec counterpart if the people of Quebec should ever express a clear desire to become independent. In 2000, Canada's House of Commons passed the Clarity Act, which stipulated the conditions for negotiating the separation of Quebec. But Madrid is not Ottawa.

Trying it in Madrid, a constant

The appearance of Turull, Rovira and Herrera before the Congress of Deputies in 2014 may be one of the most remembered episodes in the saga. But there have been a number of other failed attempts to obtain a referendum through an agreement made in the Spanish capital. Even the Catalan Socialists (PSC) took part. In February 2013, all the PSC deputies in Congress - with the exception of Carme Chacón, who did not participate in the vote - chose to break the discipline of the parent Spanish Socialist (PSOE) party by voting in support of resolutions from two Catalan parties - one from the centre-right CiU and the other from the left-wing ICV - in favour of Catalonia's right to decide its political future. Among these deputies was the current speaker of Congress, Meritxell Batet. Since then, that party discipline has only been broken on one other occasion - in the vote on the investiture of Mariano Rajoy as prime minister. The chambers of the Spanish parliament have also rejected other initiatives in this regard, such as a 2012 bill proposed by five parties, to allow the authorization of consultative referendums. In the same year, ERC raised a non-legislative motion in the house which suggested the transfer to the Catalan government of the powers to convene popular consultations. It also sank like a stone.

Nor have the expeditions been limited exclusively to the Congress of Deputies. In July 2013, the then-head of the Catalan executive, Artur Mas, sent a letter to his Spanish counterpart Mariano Rajoy, urging him to open "dialogue" and "negotiate" the holding of an "agreed" consultation, through the legal channels, "in the shortest period possible", as desired by a broad spectrum of Catalan society. Four years later, two weeks before the 1st October 2017 referendum, it was president Carles Puigdemont, vice president Oriol Junqueras and Barcelona mayor Ada Colau who sent a letter to Rajoy and king Felipe VI. The Catalan trio asked the Spanish leadership not to close the door to dialogue and expressed their desire that the vote to be held two weeks later would go ahead under mutual agreement. The answer was, yet again, the same: no.

The PSC's clarity pact

Moreover, calls for a Canadian-style clarity pact are nothing new in Spain. The left-wing Podemos-aligned Comuns have been proposing such a plan for some time in Catalonia, also without much success. There was even a deputy in the right-wing Ciudadanos party, who referred to such an idea repeatedly in his earlier days as a talk-show guest. And indeed, the PSC of only three years ago, with current leader Miquel Iceta as one of those in charge, put this possibility on the table, through a proposal which was sent for debate at the Socialist's national council. But once again Madrid manoeuvred to stop it. The pressures from the Socialists' national office again made it impossible to replicate the Quebec path on the Iberian peninsula. Since then, the PSC has abandoned the idea of supporting a Catalan referendum.

Iglesias, an expendable policy

Without support from the PSC deputies in Madrid, who have subsequently stuck religiously to the discipline set down by their Spanish party leadership, the independence movement has been left with just one major ally in the Spanish capital: the left-wing political space of Podemos and its associates. It has been the only Spanish-wide party that has supported the referendum as a solution to the Catalan political conflict. Yet now, depending on how the current negotiations on the investiture of the new Spanish government pan out, the Catalan sovereignty movement may not even be able to count on that any longer. In the last week, in a letter to newspaper La Vanguardia, Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias not only proposed submitting a coalition government to a vote in the Spanish house. He also said he was willing to sacrifice the right to self-determination if his party and the PSOE were to govern together. "We also want to make it clear that we assume that our electoral weighting does not allow the proposals of our political space to be red lines," were the words in relation to Catalonia from a Podemos secretary general who does not want to miss the last train to Madrid.