The attempt by the French education ministry to appeal to the Republic's Constitutional Court to overthrow the recently-passed linguistic immersion law promoting minoritized languages, has degenerated into a state of political chaos that puts at risk even the solidity of the majority supporting president Emmanuel Macron in the National Assembly.

Education minister Jean-Michel Blanquer chose to initiate the appeal to the Constitutional Court via a base of support in the 60 deputies of Macron's party, La République en Marche, but now it turns out that a dozen of them do not want to know anything about the attempt to block the new law favouring linguistic diversity. "The unrest is so great that several elected officials are threatening to leave the party. They either feel cheated about the actual content of the appeal or mistakenly believed that the initiative had been agreed by the whole group," says television station France 3.

The list of signatories to the appeal has only been unofficially released, and this has also been a cause of discussion, because La République en Marche does not want to make the names known officially. Minority language activists have bombarded the signatories of the unofficial list with demands for rectification. At least four of them responded that they had never even expressed their willingness to sign the appeal, and since then the controversy has continued to grow.

"Molac Law on regional languages: this submission to the Constitutional Council embarrasses the presidential majority", headlines France 3

MP Alain Péréa, leader of Macron's party in the Occitan-speaking southern department of Aude, denounced that what had happened was "a stab in the back". “There was no internal debate in the group,” he indicated. And he reiterated that he was "really angry about this dysfunction in our party, but also in relation to the message we are sending to the people who live in our territories." In similar terms, Breton MP Gaël Le Bohec, also from Macron's party, said that there had been "sabotage and manipulation". "I'm talking about sabotage because the appeal was filed a few hours before the deadline for filing such an appeal, without discussing it in our group. There have also been manipulations by the education minister with certain MPs. Some already regret their participation in the appeal,” he indicated.

Another MP from Brittany, Florian Bachelier, another Macron supporter, said he was "angry" and recalled that the appeal was propelled mainly by parliamentarians from Paris "who deny that France is rich in diversity."

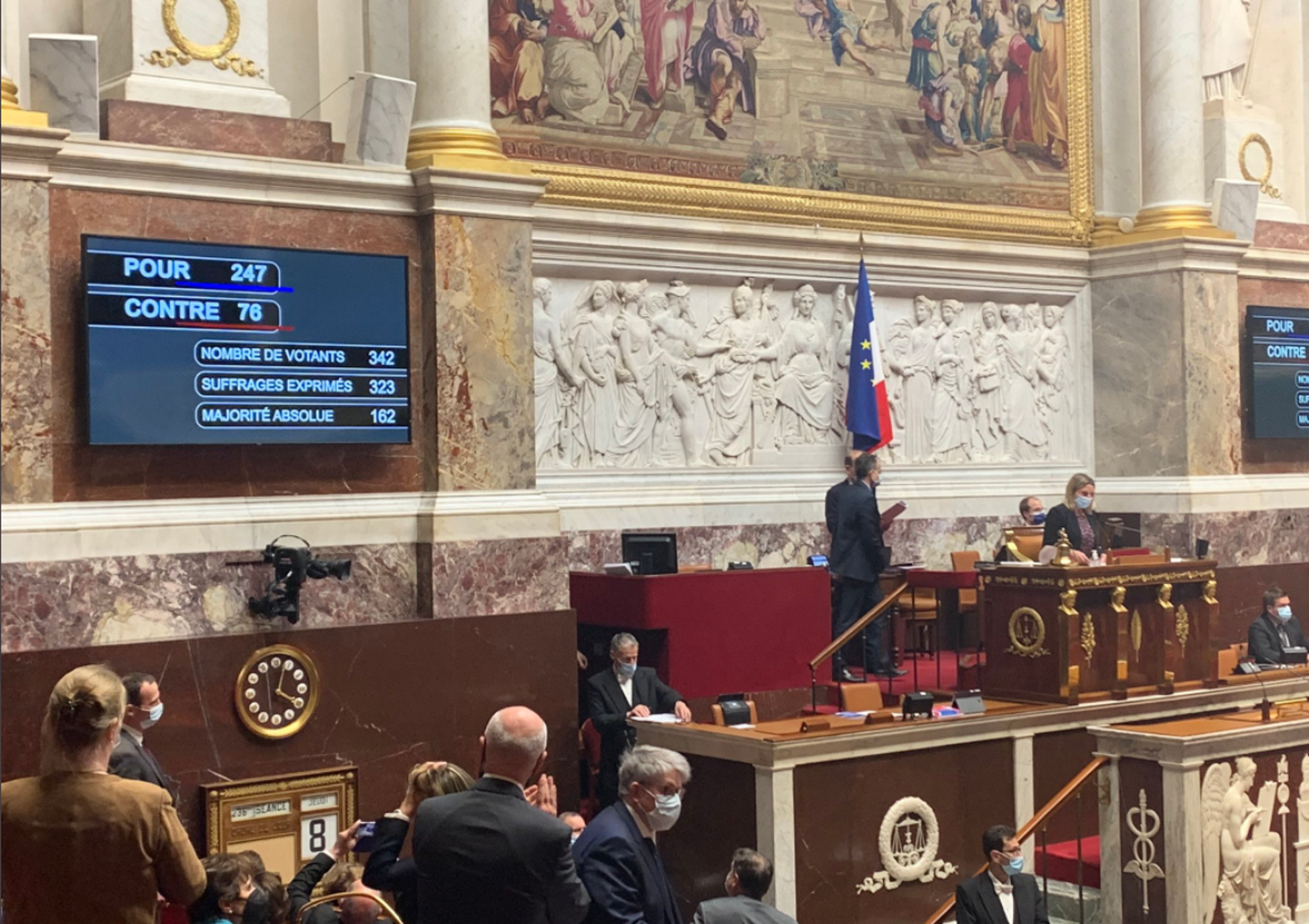

On April 8th, the French Assembly approved the so-called Law for the promotion of regional languages, which introduces immersion into public schools for the first time - that is, teaching of languages by their use as the vehicular classroom language, regardless of the subject taught. It will, for example, mean that school students in northern Catalonia, north of the Pyrenean border, will be able to have up to 50% of their education in Catalan. The proposal, promoted by Breton MP Paul Molac, was overwhelmingly approved at its second reading, with 247 votes in favour, 76 against and 19 abstentions. It far surpassed the absolute majority of 162 deputies, and means that the French Republic is finally providing some institutional support for the country's linguistic diversity in general and the specific rights of the communities which speak Catalan, Occitan, Basque, Breton, and Corsican.

The law also recognizes bilingual signage at all levels, and allows the spelling of names and surnames in ways that breach the rules of French grammar - an example being the accents in Catalan, an issue that has at times caused controversy. Diacritics not used by the French language have not been allowed until now, making it officially unacceptable for a Catalan name with an accented "í" to be used without changes, as the acute "í" does not exist in French.

The argument used by Molac, which convinced a clear majority of MPs, is that regional languages are also part of France's heritage and that their use can no longer be guaranteed by family tradition, but rather, decisive action is needed, with the role of schools being key. The most difficult sticking point was the promotion of the idea of immersion (with the nuance that it will only reach a level of 50% and that it will be voluntary), which is a successful system in southern Catalonia, as well as in Quebec with French, in Flanders with Dutch or in Israel with Hebrew. But in the end the bill won a clear majority.