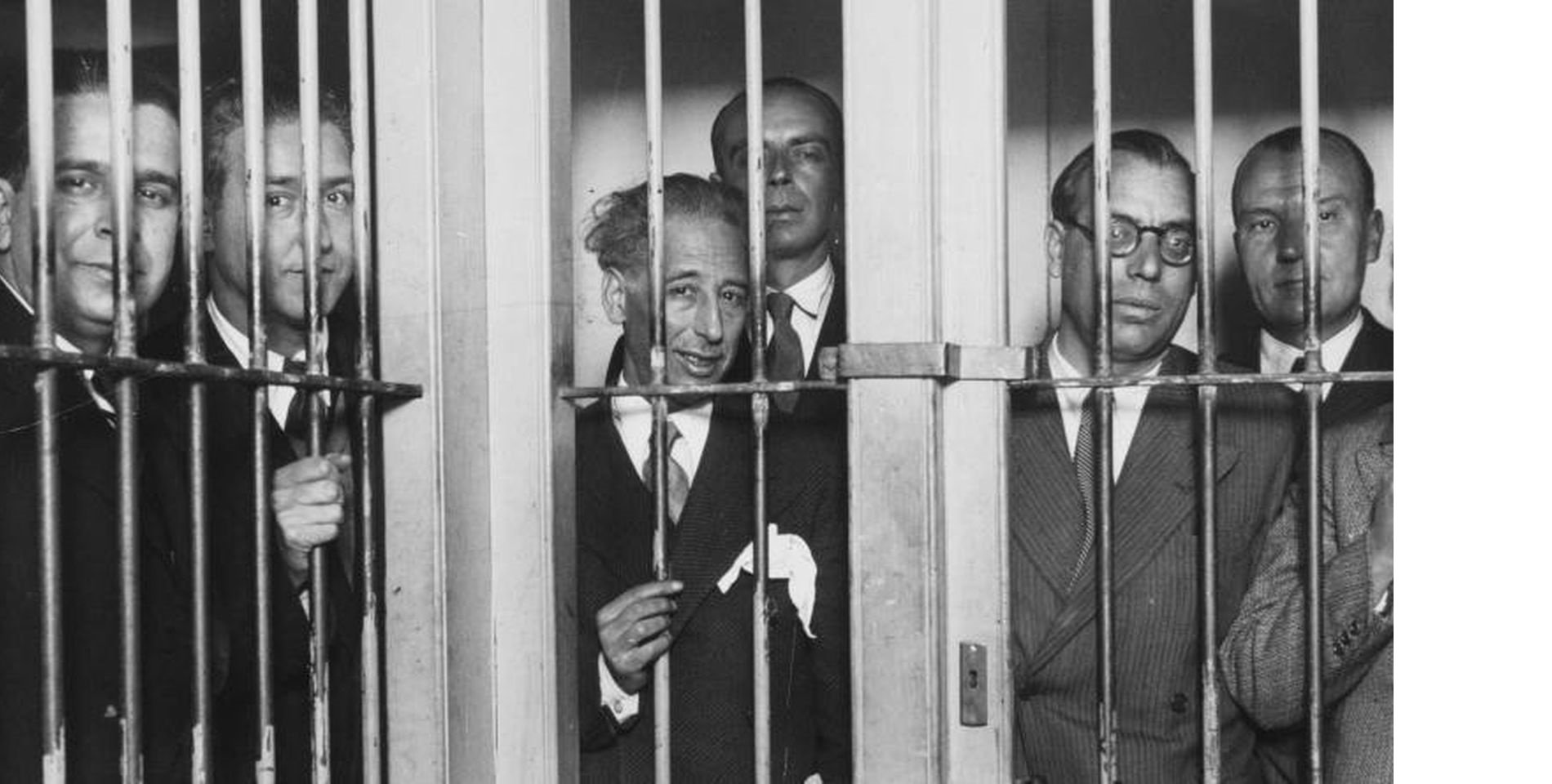

"Let's hope that history doesn't repeat itself because they could end up like Companys!", exclaimed the communication vice-secretary of Spain's Popular Party, Pablo Casado, a week after the 1st October referendum. He was comparing the current elected Catalan government with that led by Lluís Companys in 1934, which had also made a declaration of independence, as a first result of which his government was sent to prison. In fact, the ghost of those events on 6th October 1934 and –especially– the notorious image of president Companys and his ministers behind bars has hung in the air above the Catalan independence process from its very beginnings. Somehow, by repeating that everything could end up like the failed 1934 proclamation of “the Catalan State within the Spanish Federal Republic”, it seemed as if it inevitably had to be repeated.

Last Thursday, judge Carmen Lamela of Spain's National Audience sent Catalan vice president Oriol Junqueras and ministers Jordi Turull, Raül Romeva, Carles Mundó, Josep Rull, Meritxell Borràs, Joaquim Forn and Dolors Bassa to prison. A ninth Catalan politician, the former minister Santi Vila, was remanded on bail of €50,000, and after one night in Madrid's Estremera prison –where the rest of the male Catalan ministers are being held, with the two female ministers having being sent to the Alcalá Meco jail- he was released provisionally.

So indeed, the image of the Catalan government behind prison bars from the year 1934 has been repeated in 2017. We don't know the fate that awaits these new prisoners, far away from their families, friends and country, but we are able to look back and recall what happened to the seven Catalanist leaders –in that earlier time, all of them were male– who were imprisoned, tried, found guilty and finally, given an amnesty in the two-year period between 1934 and 1936.

7th October

After army general Domènec Batet, chief of the 4th Military Region, had decided to stay loyal to Spain's republican government instead of supporting the confused republican proclamation, declaring a state of war and suffocating the resistance by those who had decided to support president Companys, the Catalan president then phoned the general to surrender. In a context where the country was shifting to the right, with Europe become more and more marked by totalitarianism, where anti-catalanism had raised its head in the annulment of Catalonia's Law of Crop Contracts aimed at protecting tenant farmers, and where the Spanish and Catalan left professed their commitment to insurrection and revolution, Companys had tried to repeat the bold Catalan gesture of 14th April 1931 - when his predecessor, president Francesc Macià had declared a Catalan Republic - and Companys now attempted to refound the Barcelona-based republic, as part of a federal Spain. He had taken a notably nationalist tone, in an attempt to obtain the support of the nationalist Estat Catalá party, but he failed to generate the peaceful and popular uprising that occurred in 1931, backed by the working-class masses. Companys and his government were thus arrested by commander Fernández Unzué in the government palace, the Generalitat. That is, all of the government was arrested, with the exception of minister Josep Dencàs, one of the brains behind the proclamation, who escaped through the sewers with former Spanish military officer Arturo Menéndez.

Companys, together with his ministers Joan Lluhí i Vallescà, Pere Mestres, Ventura Gassol, Martí Barrera, all of the Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC), Joan Comorera, of the Socialist Union of Catalonia, and Martí Esteve, of Catalan Republican Action, were taken to the nearby military headquarters, the Captaincy General, on foot. In Barcelona's Plaça Sant Jaume, Companys and the mayor of Barcelona, Carles Pi i Sunyer, who had also surrendered together with the town councillors of ERC and Catalan Republican Action in the municipal government, melted in an embrace. Their “stroll” to the Captaincy General was immersed in desolation and fear. There was the fear of being lynched or attacked by soldiers of the extreme right, or that they could be victims of the notorious “Law of Escapees” - under which prisoners who supposedly attempted to flee were often executed extra-judicially, in the Barcelona of that era. The minister Lluhí was giving a slapping for refusing to participate in the chant of "Long live Spain!”

General Batet – who would later be executed by Franco for refusing to join his 1936 coup d'etat, and who was often accused of failing to assault the Generalitat and protecting the “rebels”– received them and exclaimed something like: “F*ck, Companys, what a night you have given me!" Next, he attempted to make a speech on defending ideas by democratic means, which was interrupted by Companys: “No sermons, please! Do what you must”. The Catalan government members were then transferred to the prison ship Uruguay. The rest of those under arrest –members of left-wing political parties and trade unions, police and guards – were locked up on other ships fitted out as prisons: the Ciudad de Cádiz, Manuel Arnús, Andalucía and Cabo Cullera, in the ports of Barcelona and Tarragona. Catalonia thus entered a new phase, under a state of war and with its self-government statute having been suspended.

A mediatic trial

In November 1934, the first hearing for the trial of the Catalan government was held under the competence of the Court of Constitutional Guarantees –one of the main jurisdictional innovations of the 1930s republican constitution, and the precedent for Spain's current Constitutional Court. It was the first time that such a dream team of lawyers had been assembled, to represent the Catalan president and ministers: the jurist Luis Jiménez de Asúa, socialist parliamentarian and author of much of the constitutional text; Ángel Ossorio y Gallardo, former civil governor of Barcelona many years before, who had shifted ideologically from being a “monarchist without a king” to enter republicanist territory, and who would now be lawyer for Companys; Augusto Barcia, MP and future minister under Azaña's leftist government; and Amadeu Hurtado, former MP as well as a former Catalan government minister who had represented the Catalan administration in the case of the Law of Crop Contracts.

Finally, the trial got underway in Madrid – to where the accused had been transferred – on 27th May 1935. The process was followed avidly by the press, with journalists and photographers filling all the space available to them in the courtroom. The public also queued to be able to witness that unique trial. Irene Polo, special envoy from Catalan publication L'Instant, dedicated several chronicles to it. This is how she recounted the opening session of the trial:

“The hearing had to start at eleven o'clock, but it was not until a quarter past eleven that the doors of the courtroom opened and lawyers and journalists entered the court.

"Then the accused came in, accompanied by two members of the Civil Guard. They were all clean-shaven, with their hair trimmed, and well-dressed. Especially Mr. Lluís Companys, who since P-Day [sic] in October had not been seen again with his light double-breasted jacket and that silk handkerchief spilling out of the top pocket. The benches of the dock were purple in colour. The seven accused ministers occupied the front two rows. Companys in front, as in the government. Then Lluhí, Martí Esteve, Gassol; on the other bench, Barrera, Comorera and Mestres. And behind them, the two Civil Guards standing with their Mausers.

"At half past eleven, the Chief Justice, president of the Court, Mr. Fernando Gasset, so old that he could wait no longer, rang the bell and called for the hearing to begin.”

Another journalist, Josefina Carabías, wrote an account for Mundo Gráfico and told the juiciest parts of the story:

“The chatting went on for ages, as long as the court secretary took to read out this thing they call the Judicial Report, a complete bore that you have to sit through at any trial. The silence arrived, finally, when the first of the accused rose to speak. It was Mr. Lluhí, Catalan minister of justice. Tall, erect, serious, confidently answering the judge's questions.

- What is your name? -Juan Lluhí Vallescá. - Your age? -Thirty seven.

Upon hearing this answer, some of the ladies in the public area stretched up as high as they could, because they could not see the accused well from their positions.

- He's not bad for thirty-seven, they said, and he's also in good shape.

The Justice went on: - Your marital status? "Married," Mr. Lluhí answered immediately, and it went without saying that, among the ladies in the room with good hearing and sharp eyes, there were some sudden grimaces. And they finally lost the rest of their interest in that defendant, the most elegant of all, when he answered another question: - Do you have any children? -Three children. Now the spectator ladies were almost upset. Three children at thirty-seven. It's not fair!"

At the end of the hearing, the president of the Court offered the accused the opportunity to add anything they wished. Companys made a very moving personal declaration:

"I want to say a few very brief words in my own name, and others in which I am sure that I will be able to interpret the thoughts of my ministers. In my own name, I reiterate my greater responsibility in these acts, for the reasons that my defence has already set out, following my instructions. My companions, due to the affection they hold for me, the serenity of their spirits and the stimulus of spiritual elegance, feel satisfied and hold it as an honour to share the responsibility equally with me. But this gives me a sensation that makes me declare: that this, your honour, would not be just. If anyone is responsible, it is I; or at least, it is I who has to carry the majority of the responsibility.

"Having said that, I must now, on behalf of all of us, add the following: I affirm, on our honour, because it is the truth, before the court, before the country and before history, that the motive for our actions was none other than the defence of the democratic and parliamentary republic and the freedoms which the constitution of the Spanish state has recognized in Catalonia, and which it had accepted as a commitment, and with the intention to move forward and fulfill the glorious scope of the new republican legality, the patriotic and unattainable aspirations of our land that had been constantly persecuted and mocked and, consequently, dangerously roused in the earlier regime.

"I affirm on our honour that in the meeting that the Catalan government held on October 6, in which the agreement that I read afterwards was adopted unanimously, the motivations, the analysis of the background, the arguments, the examination of the political circumstances that had arisen, all related to whether or not it was judicious to assume that there was imminent and serious danger to the liberties of Catalonia and the content of the Republic established on April 14th, 1931.

"In our political life, we have a recent memory of the Commonwealth of Catalonia, the first faltering steps of our self-government, which after a show of strength was snatched away from us without protest, an action accepted meekly; and because it happened this way, not only the form, the institution, was lost, but also our patriotic faith and inspiration for its recovery".

The Court sentenced president Companys and the members of his government to thirty years of imprisonment for a crime of rebellion. Curiously, the same sentence which the president Puigdemont and his ministers are now facing. In spite of having asked to serve their sentences together and not mixed with ordinary prisoners, rather than the political prisoners that they were, they were finally separated and distributed to different penitentiaries: Companys, Comorera and Lluhí to Puerto de Santa María, in Cadiz province; and Esteve, Gassol, Mestres and Barrera, to Cartagena.

Some unusual prisoners and a triumphant welcome

In prison, Companys received visits and read and wrote avidly. He replied to the correspondence he received and read newspapers and magazines from Barcelona and Madrid. One of those who visited most was his lawyer, Ángel Ossorio, who became a friend, and would be a defender of the president after his execution in 1940. Ossorio wrote: “With his head shaved and wearing prison uniform, he won the sympathy not only of the people of the prison, but of the entire city, which through all its media, expressed affection for him. Something quite difficult, for an Andalusian to hold affection for a Catalan nationalist”. In prison, he also received visits from journalists, who interviewed him and wrote accounts about his imprisonment.

The popular affection for Companys and his symbolic importance for the people came to light again in his triumphant return to Catalonia, after the elections of 16th February 1936, which gave a clear victory to the Left Front, the Catalan version of the Spanish left-wing Popular Front grouping, whose electoral manifesto included amnesty for the prisoners - who themselves formed part of the electoral candidature, with Companys at the top of the list. On 22nd February 1936, new Spanish PM Manuel Azaña decreed an amnesty for all the political prisoners. On 21st February, Companys and his ministers left their prison and travelled to Madrid, from where they came back in Catalonia. All along the journey they were acclaimed as heroes by the popular Spanish republican masses. On 1st March, they arrived in Catalonia, where a triumphant welcome awaited them. A welcome that culminated in the same square, Plaça Sant Jaume, where their sad downfall had been consummated, and where a tired and passionate Companys pronounced a sentence for history: "We will suffer again, we will fight again and we will win again!"