The public prosecutors serving Spain's Supreme Court have advised against the granting of pardons to the nine Catalan politicians and civil leaders imprisoned for crimes of sedition for their participation in the Catalan independence process. Sources from the prosecution service have confirmed to ElNacional.cat that "the prosecutors who argued the case against the nine jailed in the trial have submitted their reports, which are opposed to the granting of pardons to all the convicts" and that "no reasons can be seen in terms of equity, justice or public utility to grant pardons".

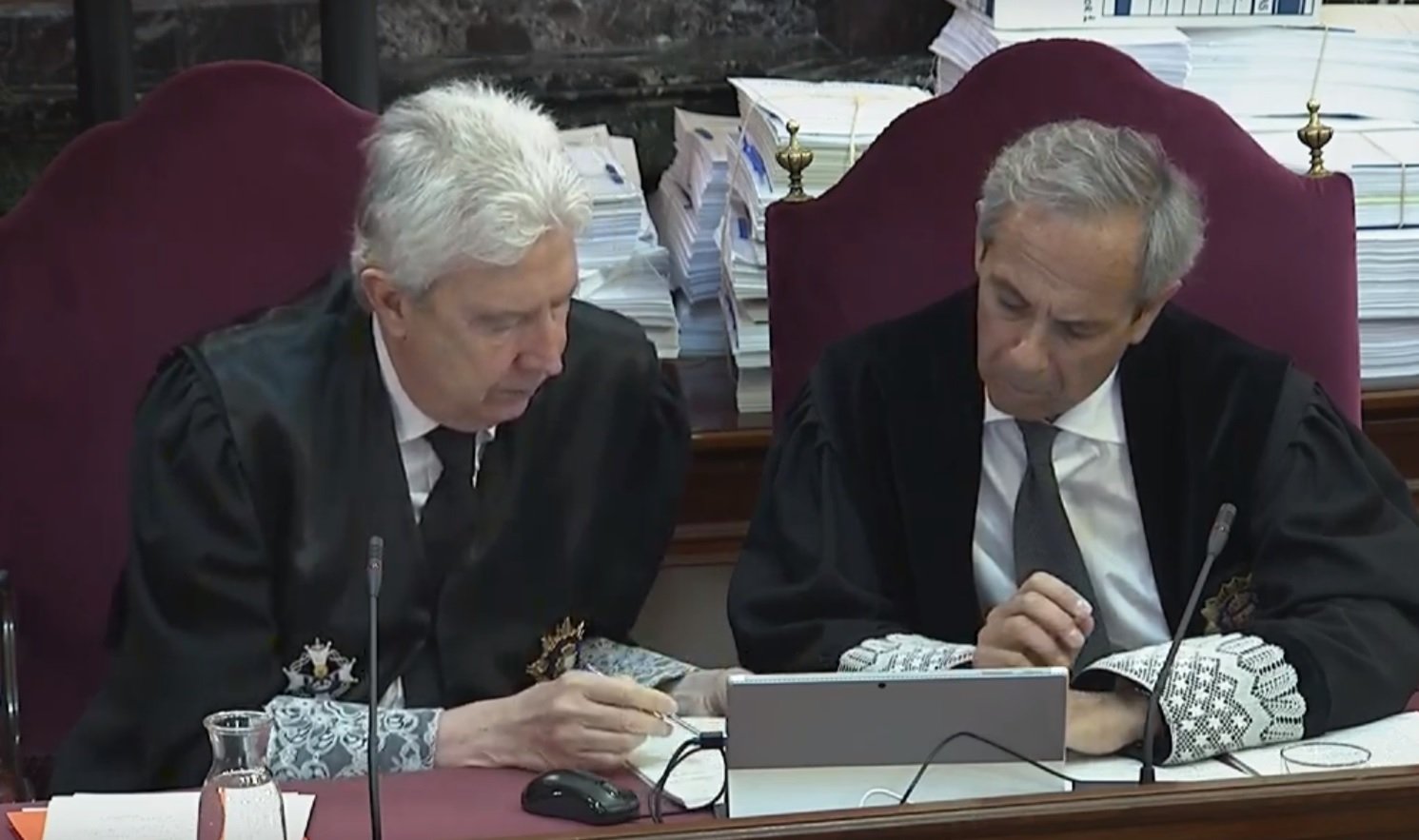

Prosecutors Javier Zaragoza, Jaime Moreno, Consuelo Madrigal and Fidel Cadena argue that the prisoners have not shown remorse, and that they have not served even half of their sentences, which are very long. These are the same four senior prosecutors who led the entire accusation against the Catalan leaders at the investigation stage and then also presented the prosecution case at the trial.

These four, who accused the pro-independence leaders of rebellion but did not convince the judges on that count, have forwarded their reports to the Supreme Court, which must now issue its own opinion and send it to the Spanish government, which makes the final decision on the pardons. Thus, it is mandatory for the sentencing court and the prosecutors to make their reports on the matter, but their views are not binding.

The public prosecutors have refused to give even a partially favourable opinion of the pardons, arguing that "this institution is of an exceptional nature and only when very special circumstances of justice, equity or public utility concur - which are not seen here and should never be identified with motivations of a political nature or derived from political agreements - should they be used to adjust the penalties envisaged."

"The penalties imposed cannot be considered unfair in view of the seriousness of the crimes committed; nor do they suffer from a lack of equity, as they comply strictly with the principle of proportionality of sentences; and, thirdly, to uphold the public utility of this measure of grace is not the most advisable when what was attempted was the rupture of the basic regulatory framework of democratic coexistence."

Consequently, the prosecutors argue that "there is no admissible reason in law to justify the pardons."

The spirit of the Constitution

A pardon, prosecutors warn, is not "a measure intended to satisfy short-term political interests, which can be arbitrarily granted as a general measure in the face of mere discrepancy with the tenor of the sentence or the sheer convenience of an overall political situation".

They state their view that the spirit of the Spanish Constitution excludes the granting of pardons to members of a government who undertook "a deliberate and planned attack on the essential core of the democratic state" thus trying to prevent this measure of grace from being used "far from the parameters of justice, as political currency offered in the process of negotiations for parliamentary support."

Accepting responsibility for the crime committed and the "decided purpose of not reoffending" are "minimally enforceable" conditions for accessing the pardon, but "none" of those conditions have been met in the case of the jailed leaders, say the prosecutors, and therefore they do not see reasons of "justice, equity or public utility" that justify this measure.

Moreover, in the case of the nine leaders sentenced to prison terms, the prosecutors appreciate "an unprecedented lack of democratic loyalty", the "rejection of constitutional legality" and the "repeated and reluctant delegitimization of jurisdictional action, alleging that they have the condition of political prisoners, denouncing that they are persecuted for their political ideas and questioning the impartiality of the judiciary."

Enforcing sentences, prosecutors argue, is an "inescapable necessity" that cannot and should not "admit shortcuts to avoid what the court ordered," in terms of periods of both imprisonment and disqualification from office, which must be fulfilled in their entirety, as the prisoners committed the crimes by "abusing public office."

The prosecutors also include in their submissions an argument against the Spanish government's plans to modify the crimes of sedition and rebellion in the Spanish Penal Code, in order to adapt them to European legal systems. In their view, the legislation of France, Italy or Belgium includes similar crimes and "it is clear that the acts for which they have been convicted are criminal in all EU states".

They assert, therefore, that "although a certain doctrinal sector alludes to the antiquity of the crime of sedition," with "nineteenth-century roots," and considers that it "does not meet the current needs of criminal policy, in order to justify the need to temper the sentences, [this sector] does not offer conclusive arguments on which to base its claim."

The prosecutors, who sought a conviction for the crime of rebellion at the trial, state that "what happened in Catalonia in 2017 was not a typical sedition offence", but rather was "much more than a serious alteration of public order", since "with the determined purpose of declaring independence (which they did) and segregating this part of the territory of the state to proclaim a new republic (which they did not achieve), there was an institutional uprising from the legally constituted powers of this Autonomous Community".

Nor do they support pardons for the three former Catalan government ministers only fined and sentenced to disqualification from office for disobedience, Santi Vila, Carles Mundó and Mertixell Borràs, because here again they see no reasons of justice, equity or public utility, which should not be confused "with motivations of a political nature or derived from political agreements".

Having heard the position of the prosecutors, the Supreme Court must now send its report, which, like that of the prosecutors, is mandatory but not binding on the Spanish government, which has the final decision in its hands.