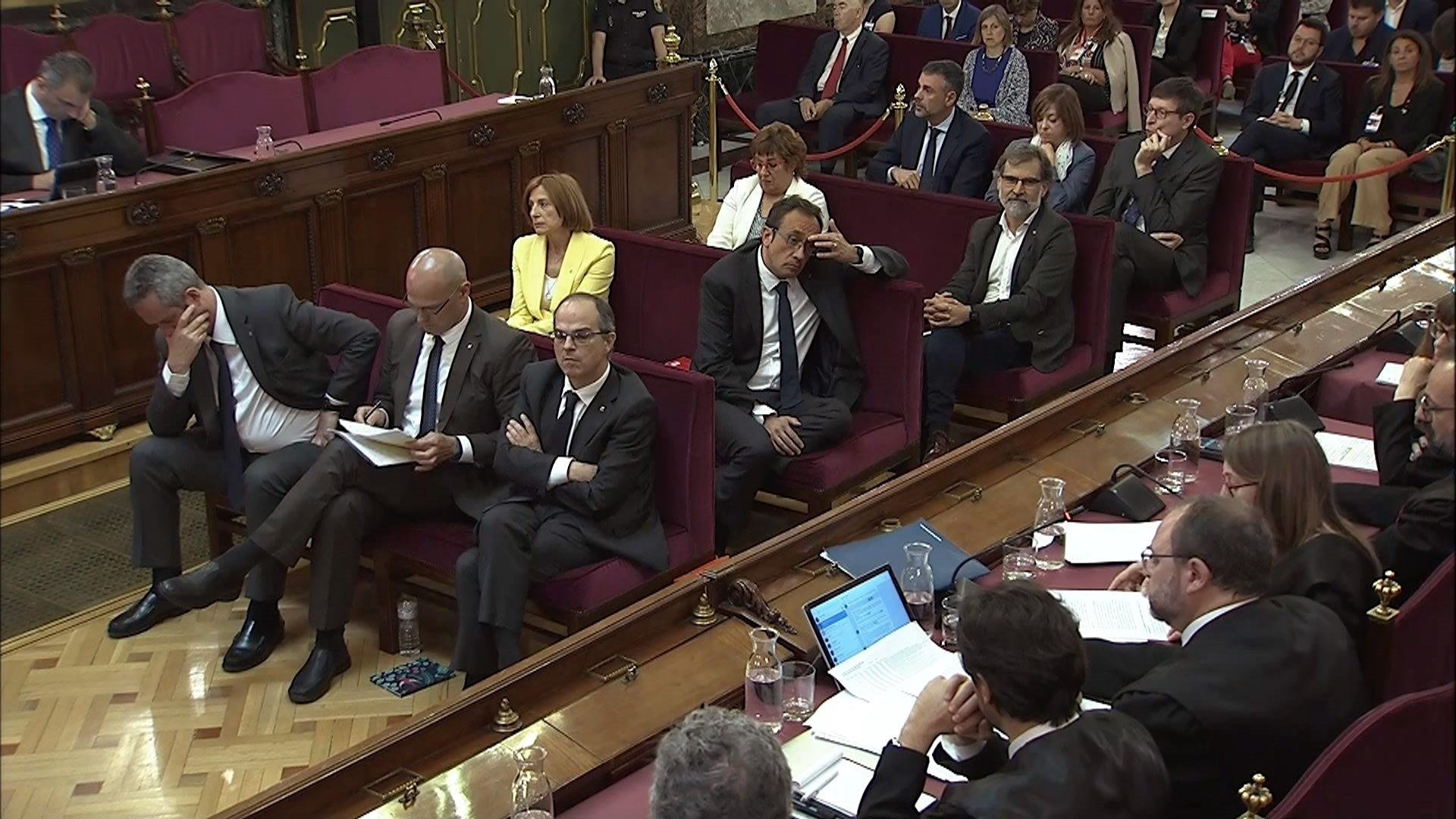

Seven separate appeals had been lodged against last June's pardoning of the nine Catalan pro-independence prisoners. But all of them, including those of the Popular Party (PP), Vox and Ciudadanos (Cs), have ended up in the waste paper bin. This Thursday, the Spanish Supreme Court's third chamber concluded its deliberations on the arguments put by the state solicitors, legal representatives of the Spanish government which awarded the partial pardons. It decided that they were sound. Thus, all appeals were rejected on the grounds that none of the appellants were entitled to lodge them. The court accordingly stripped Spain's right and far right of a judicial strategy to revoke the clemency measure and, de facto, gave free rein to the pardons. The decision comes seven months after the political prisoners were released, having served over three years of jail sentences that ranged from 9 to 13 years for sedition and misuse of funds in the 2017 Catalan independence process.

Specifically, the court decided by a majority to accept that "each and every one of the appeals lodged" lacked active legitimacy. Seven had been presented: the anti-independence association Convivencia Cívica Catalana; the Cs leaders, Inés Arrimadas, Carlos Carrizosa and José María Espejo-Saavedra; far-right Vox as a party; the PP as a party; present and past PP deputies in the Catalan Parliament Alejandro Fernández, Santiago Rodríguez, Andrea Levy, Juan Bautista Milian and Lorena Roldán; the former delegate of the Spanish government in Catalonia, Enric Millo, and the association Pro Patrimonium Sijena y Jerusalén.

The question of recognition of the legitimacy of appealing was the first step. According to the doctrine of the Supreme Court, political parties are not legitimized to make such appeals. The doubt was with respect to Vox, which had also led a private prosecution in the trial of the pro-independence leaders. In the end, however, the party's appeal was not admitted either.

When an appellant's legitimacy is rejected, the Supreme Court does not even have to enter into the substance of the matter; that is to say, it has not had to decide on whether the pardons were granted correctly by the Spanish government or not. Only the decision is known today. In the coming days, the Supreme Court will announce the full content of its ruling and, therefore, the arguments that led to today's decision.

Supreme Court opposed pardons

At the time that the Spanish government broached the possibility of pardons for the leaders who took Catalonia to the verge of independence in 2017, the Supreme Court recommended against the granting of pardons. In its report, which was mandatory but not binding, the sentencing court considered that there was no breach of the principle of proportionality of the sentences to which the political and civil leaders had been convicted, that there was no evidence or indication of repentance on their part, and that the arguments on which the various requests for pardons made by third parties were based blurred the meaning of the pardon because they depicted a collective criminal liability and, moreover, that the Spanish government had sought to correct the ruling handed down by the Supreme Court.

Even the most senior figure in the Spanish judiciary, Carlos Lesmes, president of the General Council of the Judiciary and the Supreme Court, went so far as to speak publicly. "A pardon, when there is no concord, is difficult to accept," warned Lesmes, in the weeks leading up to the granting of the pardon. He continued to level criticism against the measure months after the fact.